Unhappy Medium

John Haberin New York City

Frank Stella's Bamboo and Kurt Schwitters

One wrestles with massive industrial scrap like animals that have escaped their cages. The other turns a fragment of a word into the totality of his art. One demands an art apart from and larger than life. The other slowly amasses the record of a civilization.

Frank Stella and Kurt Schwitters both cherish leftovers like elements of a lost language. Both seem content to let their assemblies make themselves. And both have an unlikely faith in painting. After that, any resemblance is purely coincidental—or is it?

One insists that he has never stopped painting. So how can his constructions, now unpainted, move freely in the round? The other gives his medium, collage, a nonsense name. So how can he sustain painting as a basic creature comfort?

Two lovely gallery shows get one puzzling over a gap of over half a century. I ended the spring of 2003 wondering at the simplicity of such words as painting or appropriation. Thanks to exhibitions in 2005 and 2006, extending one's view Stella's career at either end, one can keep puzzling even longer. A postscript even has me imagining Stella as architect.

Defying gravity

Frank Stella has remained his own man, and you know men. His early black paintings, starting before 1960, still look defiantly simplistic. They assert their presence quite as much as modernist painting. The industrial-strength oils pick up where enamel house paint for Jackson Pollock left off. Black, defined sometimes as the absence of light, positively glows. Between stripes, the unpainted canvas shines with a softer white.

His discovery of the unpainted canvas begins from the moment he landed in New York. Even the titles of his paintings from 1958 often refer to New York streets and neighborhoods, at a time when he first took a studio in downtown Manhattan. That year stands between his college graduation and the stardom that his black paintings earned. I often think of Stella as an overnight success. Seeing his work from 1958 together, one realizes that it took him, well, a few months. And no wonder, for the stripes and smears of dull color show nothing of the deductive logic or hypnotically stripped-down images that one expects.

What they do show is how he found his way. In particular, they trace the symmetries and fields of paint to two influences, Mark Rothko and Jasper Johns. One can imagine Johns flag paintings as seen through Rothko's abstract, painterly eyes.

Perhaps more accurately, one can see them both as if Clement Greenberg had eliminated the "mistakes." The stars have vanished from the flags, and the resultant fields have moved closer to the center. The stripes have spread and deepened to displayed the painter's touch, and yet every hint of personal meaning has effaced itself. Even when he pulls off some assemblages, after Robert Rauschenberg and Rauschenberg collaborations combine paintings of those years, Stella seems desperate to lend them sufficient gravity.

In short, Stella seems to want pure painting, but also Johns's way of putting icons of Modernism far too close for contemplation of the sublime. And in a few more months, he gets it. Meanwhile, however, these early paintings make one aware of another influence, one perhaps more at home in art today. If the titles refer to New York, the dark parallels make me think of steel grills drawn down at night in an industrial area. Moreover, the loose execution could almost look forward to Bronx and East Village graffiti.

The cheap materials, including oil and enamel, certainly refer back to Jackson Pollock, but also to the needs of artists one step off the street themselves. The work shy away from humor, much to their detriment, without gaining the blackness of his breakthrough. Yet one can almost look ahead to the exuberance of Stella's more recent thrust into three dimensions.

Self-criticism without the apology

I say almost, because by 1970, his designs still derive methodically from the frame, but both frame and design spill every which way. Colors leap over one another and across an entire room. They tilt sharply in and away from walls. They turn an artist's tools—rulers, protractors, French curves, or die-cast webs —into full-scale models of laminar flow. Titles after Polish villages and exotic birds hint at their architectural scope, historic ambitions, and messy flight patterns. They offer the first hint that his work might defy gravity after all.

Stella went to Princeton, where one knows the rules. Greenberg, he learned, had called for painting's "purity" and "self-criticism." Stella, too, wants painting to manifest itself, to get past the unthinking kitsch all around him. However, if Greenberg's vocabulary sounds like the same Stalinist purges that once eliminated abstract artists, Stella has nothing to confess.

He definitely is not confessing to Minimalism or installation art. Others of his generation follow the logic of a formula and the shape of room. Stella, however, has painting on his mind—independent and in one's face.

Sol LeWitt covers the wall, but he leaves the execution to assistants. Stella's machines, like the pencil lines visible between the stripes, flaunt their handmade look. LeWitt makes formulas so elaborate that they blur the line between logic and chaos, and other Minimalists wrote of entropy. Stella stays the control freak. Minimalism, like a floor piece by Carl Andre, remains open to time, space, perception, and the viewer's body. When Stella fills a room, he does it with objects and paint.

Stella has lectured on the primacy of painting and its inherent logic. Like Leonardo long ago, he worries about rivalries of the arts. He has criticized the Museum of Modern Art, an early supporter, for losing its direction. As if in reply, the Modern placed him at a critical point in its survey of the twentieth century. As with the other great exponents of shaped canvas, Elizabeth Murray and Charles Hinman, it seemed unsure whether Stella belongs with the present or the past.

Perhaps Stella feels the same way—and proud of it. Postmodernism teaches that a work's logic, pushed far enough, blows up its face. Stella suggests something similar about a career. With each step, he just pushed the envelope a little further. At some point, however, it hardly makes sense to call the paintings literal—or even painting.

Drafting without the tools

Only at what point? Stella's body of work seems full of sharp breaks. Only where?

His logic of the frame keeps going. Eventually, however, frames vanish altogether except as an idea. Perhaps they served as one all along. When protractors and French curves tower over people, art no longer exemplifies its making: it represents. For all his purity, he has much in common with Chuck Close's allusions to photographs. For all his high culture, he puts on a show akin to Roy Lichtenstein with his mammoth Brushstrokes.

A series of the late 1990s draws its titles from Moby Dick. Earlier, Stella exhausted the vocabulary of drafting tools. Here he creates an anthology of painting technique. He draws in paint, drips it, and layers it with care. He slathers it on and etches it away. The great whale looks anything but white, and Stella has no one left to struggle with but himself.

Even the titles belie Stella's infamous maxim, "what you see is what you see." A book about the series assures one of a match between episodes in the novel and the paintings. Not that I can spot the links between text and image. For that matter, I can hardly keep the images separate. Then again, I hardly know which most undermines literalism, a narrative or its failure. Either way, art has a dangerous way of multiplying signs.

The artist pays a price, however. I do not mean his stubbornness. I do not mean his fall into the chasm between old-fashioned painting and new-fangled installation. In 2001, his dealer borrowed an adjacent warehouse to display such extravagantly large paintings. I could hardly tear myself away from examining each piece up close for all their variations in surface and space. A month later, however, I could no longer picture so much as a single painting.

As usual, if I have questions, Stella has answers, only not necessarily to what a mere critic might ask. In 2003 and 2005, he again exceeds his own limits. Both times, he takes over his dealer's regular space, including half the office. He exceeds the limits in another way, too. In these paintings, the paint vanishes.

Painting without the paint

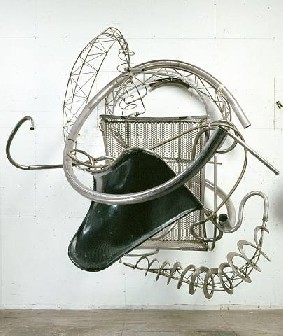

Some hang from the ceiling. They look massive, but they rotate at the slightest touch. Others project so far off the wall that one can get behind them. He may not call them sculpture, any more than Judy Pfaff with her own untamed painting, but they definitely get around. Surprisingly, it leads to Stella's most memorable work in years. Along with the paint, he seems to have stripped away layer upon layer of old habits and dusty ideas.

The shift in 2003 returns him to his Minimalist roots. One can spot the recurring elements—the rods, the coils, and the mesh—that define this series. One can see again the image and object. They face the viewer once more, eye to eye, even in the round. One work, I could swear, looks like a helmet. For the first time since Stella's exotic birds, I can see lightness and a connection to life, befitting a series named after bamboo.

It also points back further, to Modernism. Coils suggest a rearing animal from Raymond Duchamp-Villon, and the helmet makes me think of Constantin Brancusi. The exposed, jagged edges, bare metal, and open forms suggest Woman with Her Throat Cut, by Alberto Giacometti. Talk about art's cutting edge. The used engine parts suggest Marcel Duchamp and his machine imagery. Then again, the whole impulse to strip away old layers sounds like the avant-garde.

It points forward, too, however, to postmodern delight in illusion. Did that old, shredded metal really once serve as a lamp shade? The forms have a cartoon life of their own, rising out of their cages. I wanted to rescue the lamp shade, to feel the bamboo, and to pet the animals. I wanted to touch the aluminum's raw edges. Giacometti's horror seemed far away.

Not that the story promises to end any time soon. For at least one moment during the 2005 exhibition, I was ready once again to accept Stella as that tired, overblown institution that even the Museum of Modern Art started largely to ignore. Again I saw, if that word makes any sense for something so expansive, his impossibly rough-hewed painted metal constructions. And again I wondered what had happened.

Almost flat compared to much of his other recent work, the 2005 series still earns the name surface, and Stella throws at it everything he has. The artist seems to have traded the iconic stature of his early geometry and the remorseless logic of his increasingly complex constructions for sheer firepower. Who cares these days about iconicity, geometry, logic, or even the future of abstract art anyway?

Stella meets Spiderman

I should give him more credit. For Stella to revel in splatter, while pretending to let his shapes govern the assembly, sets up a logical conundrum already. For him to suggest Abstract Expressionism has some well-considered irony, too. Besides, the work's deliberate crustiness may make it the most, if not only truly contemporary work in the show. I could almost imagine it in "Greater New York" alongside Kristin Baker's acrylic on PVC.

Still, I found myself admiring more the unpainted work that otherwise fills the gallery. Partly, as with Stella's 2003 show, I still prefer the paradox of painting's logician driven by his own logic to abandon paint. Partly, too, I appreciate almost a recovery of modesty after the factory parts, sheer variety of painted surfaces, and references to Moby Dick characteristic of the 1990s. He seems to concede that his chase for the great white whale has become an impossible obsession. Then again, one should never accuse Stella of lacking self-awareness.

Mostly, however, I just liked the pieces as sculpture and as objects that had not really given up on color at all. Largely simpler in outline than in 2003, their coils typically spiral up around a central axis, like some kind of electrical machine working to its own ends. Maybe Doc Ock created it after losing out to Spiderman.

Along with metal that does reflect light and color, they incorporate for contrast gently curving sheets of carbon fiber, less like airplane parts than oversized bicycle sheets. When I saw Nancy Rubins at Kasmin later, I thought of a Stella imitator with the wit to make works that seemingly had to be held down. These float upward.

Could I still explain to an artist now how Stella once got to speak for painting? Could I explain it to myself? Perhaps I should ask instead why anyone would bother.

Surrealism's threat has gone. Art and culture still have a funny way of taking over from humanity. At last, however, humans will not mind one bit.

The morning papers

Before 1920, another artist developed a twin obsession with messiness and control. And he, too, makes it tough to tell the two apart. In 1919 Kurt Schwitters cut four letters from an advertisement, for use in a collage. The syllable stuck with him for the rest of his career.

Schwitters did not title every work Merz. The term became him all the same. At times he even took it as a middle name. It holds together what Ubu Gallery calls "Paintings, Drawings, Objects, Ephemera." One might well add poems, cutouts of wood, and the seeming permanence of memory. As with Stella's career, who can say where one leaves off and the next begins?

For starters, Merz means a fragment of the world, in two dimensions. As in abstraction right down to Stella, each object, each pencil stroke, and each touch of paint stands on its own. These fragments he has shorn against his ruin, and one lingers a long time over their gentle browns and delicate textures.

Merz also takes on the real world, between the disasters of World War I and the Great Depression. Part of a company name, "Commerz- und Handelsbank," it accepts the anonymity of advertising, printing, mass reproduction, and corporate power. It accepts the aging and decay of these tarnished rituals, along with the dirt and broken wire left over from war. For all his care, Schwitters does not allow an easy escape into fine art.

Merz also amounts to type on paper, a sign without a signified, an artist's book without image or story. Schwitters experimented with repeated strings of typewriting as poetry. Conversely, the constructions could pass for real papers, the material behind a still life. I think of each work as a tray, like an in-box today. Schwitters, were he alive, could present it each morning to a German businessman. I assume, of course, that a proper bourgeois could find his way past the 59th Street Bridge and squeeze down Ubu's new winding stairs.

Then, too, Merz makes no sense at all, and its very nonsense leaves room once more for play. His newsprint rarely spells out political points or puns. German Expressionism and Dada knew herz and schmertz, heart and pain, all too well. In place of their pessimism, Schwitters evokes their sounds as a comforting cliché, like moon and June. Life goes on somehow, and so, after all, does painting.

Fits and starts

Stella might agree with that, were he to turn down the volume for a minute. But then, for both artists, simply going on can involve tantalizing fits and starts.

Stella's logic takes painting on an unlikely path to Postmodernism. Kurt Schwitters dedicates Dada to tradition. I savored the woody tones—and sometimes wood itself—lacking in Stella's bamboo. Collage never has to give up the handmade, because it begins as art.

Opposites may attract, or they can cross in the night. I left thinking of what the two artists have in common. Consider their different inheritance from Modernism—and from the founder of collage itself.

Pablo Picasso borrows the feel of crumpled paper to represent a hat. His fragments tend to avoid the frame, as if they have no idea what to do without one another. Casting ideas and representations against one another, Schwitters lets paper look like paper, even as its edges fade into paint or cross the frame. Schwitters, like Stella, appreciates each thing for itself.

Cubism separates the texture, shape, name, and sound of a violin. It unsettles any idea or point of view. Schwitters starts with a single vision, like a still life seen from above. Then he turns it ninety degrees, up on the wall. Facing the viewer, it looks as frontal as Stella's protractors—and as difficult to confront.

The more Stella or Schwitters lets a medium speak for itself, the harder it gets to know who is speaking. Maybe Modernism understood this all along. "Is the existence of limits serving to distinguish between the various arts also a condition of the possibility of value within them?" Greenberg meant that as a rhetorical question, a matter of ethical and cultural as well as esthetic values. Once an artist poses questions, however, art has a way of taking them literally.

A postscript: two villages

You can imagine the story. When her boyfriend landed in jail, she felt doubly cheated. Somehow, he had gone from neurotic to institutionalized without passing through full-blown hallucinations. One could feel the same way about "Frank Stella: Painting into Architecture." How could Frank Stella make the transition so effortlessly without first producing sculpture?

As Stella saw it, he never needed sculpture. Painting creates, even demands, its own space. It does not need recourse to illusion or to sculpture, but it still might need some help. Over the years, help has ranged from shaped canvas and tilted planes to twisted and welded metal covered in a library of painting techniques—or in nothing at all. Stella's earlier stripes help, too, by running parallel to the frame, in black and industrial hues that lift them further into the room. Bare canvas and pencil lines visible between the stripes insist on the object and its making, and so does the wood of the stretcher, set thick dimension out.

Stella's industrial materials give new meaning to the word machine, once applied to large academic painting. They have also made painting's former savior into something of an institution. Could they make him an architect as well? In this exhibition, he has aspired to one for almost forty years. The Met surrounds recent architectural models with painting from as early as his 1971 Polish Villages. When he alluded to communities destroyed by conquest and war, could he already have envisioned a cure?

Like an architect and unlike many a Minimalist, Stella shapes a space apart from the work's surroundings. His freely curving metal can even approach Frank Gehry's exteriors of the same years. So does its ability to guide one along surprisingly well defined paths. His choice of projects plays to that strength, with a rambling park, an auditorium, and split-level housing. They provide designs for living and breathing, not for sitting and working. Younger artists may think of him as corporate, but I cannot yet imagine him tackling an office complex.

A comparison to Gehry, however, overlooks that continuity in his career. Like his abstract painting, Stella's architecture reverses one modernist credo, form follows function. For Stella, form guides every twist and turn, to the point of creating its own function. It creates and connects spaces for strolling and for shelter. By contrast, postmodern architecture highlights a disconnect, as with the embellishments of Michael Graves. Stella has criticized Gehry's Guggenheim Balboa for not fully serving the art within.

Still, no one is rushing to build a Stella village, because at heart he is still painting. On the roof of the Met, he does contribute this summer's sculpture, but the curves look lovelier in the paintings and models downstairs. With each gallery show, he grows toward his most sculptural painting yet. Yet for all the three-dimensional drama of his hulking, curving painted metal in 2003, form still ruled, right down to quotes from design templates. In his 2005 show, the unpainted surfaces rose up on their own, almost like robotic life. Maybe his work should never become sculpture or architecture, because then it will have to sit still.

Frank Stella's "Bamboo" series ran through June 18, 2003, at Paul Kasmin and, two years later, his "Balinese Character" series ran through May 14, 2005. His 1958 paintings ran at Harvard's Arthur M. Sackler Museum through May 7, 2006. "Paintings, Drawings, Objects, Ephemera" by Kurt Schwitters ran through May 23, 2003, at Ubu. "Frank Stella: Painting into Architecture" ran at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through October 28, 2007, in conjunction with rooftop sculpture, while smaller work ran at Kasmin through July 6. For associations with the German language, I owe a debt to Martin Herbach. Naturally he bears no responsibility for how I have abused his thoughtful hints. A related review takes up a Stella retrospective.