Getting the Message

John Haberin New York City

Nicole Eisenman, Gender, and the New Museum

Martin Wong and Art After AIDS

There are allegories, and then there are "al-ugh-ories." Allegories are so yesterday, laden with messages that one would chose to forget. Now Nicole Eisenman puts the "ugh" in allegories, and nothing is hipper than a little condescension. Yet she has a message, too, about gender and sex.

Eisenman may have her "Al-Ugh-Ories," but do not go to the New Museum expecting parables of eternal life or the passage to another world. Everything there is as real as the trials and triumphs of women, only with the deck for once stacked heavily in their favor. That applies not just to her, but to all six shows on five floors, with women from Eastern Europe like Andra Ursuta and Goshka Macuga. Meanwhile gender, gay identity, and New York communities take on a moving difference with Martin Wong in the Bronx.

Battles of the sexes

Do women get the short end of the male stick when it comes to exhibitions? You must be thinking of the Museum of Modern Art. Now the New Museum, where triennials and solo shows normally spill over more than one of its awkward floors, devotes all its spaces to women. That includes not just its big boxes, but also the grand but narrow stairs, where Eva Papamargariti hangs colorful banners. It includes the lobby gallery, where Cally Spooner choreographs a silent battle of the sexes. It includes the education department upstairs, where Beatriz Santiago Muñoz translates a classic feminist novel into new media and tales of home.

Speaking of allegories, plainly the museum is sending a message. It does so as well with its international cast. (Did you forget that Eisenman, the child of German Jews, was born in France?) It may add to its challenge to New York that none is from the Third World. Papamargariti, from Greece, imagines a world between nature and abstraction but overflowing both, starting on video before becoming fabric. Spooner, a Brit, makes the space off the cafeteria all the plainer by soundproofing the walls, before inviting her cast of men and women to mime rituals of seductions and war.

Are these allegories after all? Spooner's dance is elegant, even when the dancers are butting heads, but literally slow going. Muñoz builds on Les Guérillères, about a world after the fall of the patriarchy and still devastated by war. Monique Wittig's 1969 prose is way more experimental than that sounds, but the video's three channels set women up to do things like pet goats and view the sea through colored filters. It also sets them in the artist's native Puerto Rico, where the United States long pulverized the land all on its own. The site served as a bombing range.

Eisenman has her utopias and dystopias as well, but gender here is always at issue, and so is First World power. Wittig was a lesbian and feminist theorist, and Eisenman identifies herself as a queer artist. Speaking again of allegories, the struggles at hand keep taking on spiritual dimensions, too—and Spooner's dance first took place in a historic Dutch market overlooked by saints. Andra Ursuta portrays women as scornful matriarchs but also refugees from patriarchy and money. Born in Romanian, she casts bronze statues in folk garments, beneath shawls made of coins. Looming over them, a bulbous eagle occupies the center of something between a basketball backboard and a flag.

They also occupy a landscape both alpine and allegorical. It consists of climbing walls, broken now and then by degraded skeletons or flesh in white. Amidst it all stand jagged white obelisks like diminished gods or ghosts. Goshka Macuga, although born in Warsaw and based in London, completes the journey from the art of Eastern Europe to the United States. Her large tapestries, beginning as photo collage in black and white, include Back Forty, the Midwestern woods that right-wing lunatics have claimed as a refuge—although signs proclaiming that Art Is Power and International Bankers Control Our Nation number among its protests. Other tapestries display a press conference at the United Nations, in front of a replica in fabric of Guernica, where Colin Powell was about to lie on behalf of war, and Afghanistan, where artists and intellectuals camped on cold sands by the ruins of a palace.

Do these shows sound as ponderous as allegories as well, not to mention as obscure? Macuga calls her work "Time as Fabric," just so you know. She also weaves in a Hopi snake ritual and, at the show's center, an entire stage set with space for Marina Abramovic, Richard Artschwager, a legendary art historian, and photo replicas after Laocoön and Roy Lichtenstein. There is no trusting to art. One can race through all five floors all too quickly. Like it or not, one will still get the message.

Putting the "ugh" in allegory

Actually, allegory has been making a long and determined comeback, with or without a message. Modernism punctured expectations of realism long ago, and Postmodernism elevated rhetoric above reality as well. Paul de Man titled his classic of deconstruction Allegories of Reading. Nicole Eisenman, though, has something else in mind. "Al-Ugh-Ories" has tale after tale of mortality and temptation, and nothing tempts her characters more than death. It comes in the form of unnatural disasters, capitalism, and lust, and women put their flesh on the line to attain it. They also know better, not to mention way better than men.

True, death looks a little bored as a woman raises her sunken eyes, her bloated flesh, and a toast. A woman in a busy beer garden catches death in a kiss. Another tops her nudity with a bowler hat, surrounded by a male corpse and her art books. Still, you know the real problem. It could be the helpless tycoon dropping his trousers, while an entire Depression-era crowd moves determinedly forward. It could be the pathetic child dropping his pants beyond his bulbous red nose. It could be the male looming over a woman as, the allegory promises, Commerce Feeds Creativity.

The tycoon finds his buttocks on the front of his waist, but then no doubt he has his head screwed on backward figuratively as well. An entire alpine village finds itself waist deep in pink flow. Meanwhile women do their best to cope. One even reprises the old fashion of playing Hamlet against gender, robed in black. Still, creativity is always under threat, and you know why. As that pathetic child's t-shirt insists, I'm With Stupid.

If you recognize the roles, it will be not just because you know what to think. Sources include popular culture along with German Expressionism, Impressionism, and Surrealism. The Depression retinue imagines a lost Renaissance painting by, rest assured, Hans Holbein in Tudor England—and the beer garden may well borrow from Edouard Manet. Yet one of the more dignified if still altogether puzzled males is Thing, from the Fantastic Four, in From Success to Obscurity. Eisenman has moved away regardless from more literal quotes since 1996, when she posed a nude sacrificed to a sea monster after J. A. D. Ingres, as Spring Fling. She is also trying her hand at sculpture of, naturally, primitive men.

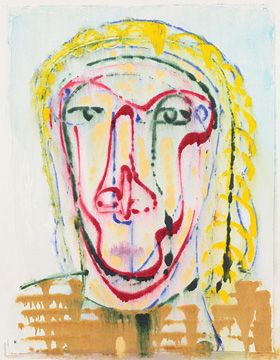

You may recognize the lavish brushwork and casual realism. You may recognize the dysfunctional communities and the orange, green, and swollen flesh. Still, these are al-ugh-ories and no more. Eisenman has brought a deep ambivalence toward tradition with a family Seder at the Jewish Museum before, and she seems out to capture a younger New York more sympathetically at her gallery in Chelsea. She has riffed on masks in the manner of outsider art, graphic novels, Alexej von Jawlensky, Blue Rider, and more. MoMA admired their diversity enough to include them in a display of abstraction and hybrid forms in "The Forever Now," and they appeared in the 2012 Whitney Biennial as well. As curators, the New Museum's Helga Christoffersen and Massimiliano Gioni seek something wilder, more playful, and less forgiving.

They risk cultivating something glibber instead. One can look for a role model in lesbian sex beside a nightstand topped with Albrecht Dürer, the Iliad (the Fagles translation), and Maria Vargas Llosa. One can relish the raw earth tones of The Work of Labor and Care. One can look for signs of the artist's struggle in a messy studio or, with a family and cans of tuna, settled in for the long haul. One will, though, find barely twenty paintings, in no particular order. One may have to work a little harder to see past the allegory and the fashion.

Like a ton of bricks

New York hit Martin Wong like a ton of bricks, and he loved it, but he never forgot its dangers. He hardly could, arriving in his early thirties in 1978, in the city's darkest years. He was staying in an SRO on the Lower Manhattan waterfront when he painted a pretend headline about fiery mass deaths in a Roach Motel. The words cross a brick wall, much like a painted bullet from those same years ricocheting off a heart. A later work does real damage to a heart, this time with a chain saw. Apparently New Yorkers were not so hard of heart after all.

Brick walls are a means of exclusion, and Wong painted many of them aligned with the canvas. Later he turned to steel gates and closed churches, one with an unwelcoming title ending Inc. He had every reason to know exclusions. An openly gay male, he moved after a few years in New York to the Lower East Side—and I mean its far east side, where even now galleries fear to tread. There he lived as a Chinese-American artist and a Loisida in an almost uniformly Latino neighborhood, and he thrived on his own terms. He exhibited at ABC No Rio on the fringe of East Village art.

Brick walls are a means of exclusion, and Wong painted many of them aligned with the canvas. Later he turned to steel gates and closed churches, one with an unwelcoming title ending Inc. He had every reason to know exclusions. An openly gay male, he moved after a few years in New York to the Lower East Side—and I mean its far east side, where even now galleries fear to tread. There he lived as a Chinese-American artist and a Loisida in an almost uniformly Latino neighborhood, and he thrived on his own terms. He exhibited at ABC No Rio on the fringe of East Village art.

He also entered a relationship with Miguel Piñero, the Nuyorican playwright, who came with tales of other impenetrable walls, in prison. Wong made those his own, too. His prison paintings look downright idyllic in their broad spaces and nubile men, give or take UFOs in the sky. Brick had already been for him a means of inclusion as well, leading the eye to interiors and to himself. He paints it lovingly, in warm colors, lingering over shadows and serious damage—even when it covers ovals like vanity mirrors, as yet another effacement. Often additional brick acts as a picture frame, set apart from the central subject in convincing illusion.

Brick and solidity give way later in the 1980s to deep blue skies and fantasy, with text art as a variant on Beat poetry, in a concurrent show in Chelsea. He turns to New York's Chinatown just a few blocks south and to memories of home in San Francisco, in still another search for himself. Chinese women display themselves in rows of windows, above cheap jewelry stores and angled streets. Constellations mark the skies with their names and outlines, although (this being the inner city) little in the way of stars. Still, however feverish, Wong never quite lets go of the somber hues, the barricades, and a grim sense of humor.

As the Bronx Museum makes clear, he had identities and interests to spare, like so much of art after AIDS. He produced theater design in California, which must have helped him understand Piñero, and he studied ceramics at Humboldt State University. The Whitney included him in "Blues for Smoke," its show about art and jazz, and a repeated motif of sign language may hint at still other gestures and other messages never expressed. Early self-portraits adopt a sketchy Bay Area realism, his palette of red and black looks back to Marsden Hartley, and the bullets and text-ridden walls show an interest in cartoons and street art. Still, Wong prefers texture and realism to the slashing improvisation of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Even the lettering looks neat and clean for graffiti or graffiti art, sometimes in Spanish and sometimes marching around the painted frame.

He has become something of a gay icon, too, as for Julie Ault in the 2014 Whitney Biennial, and he died of AIDS in 1999. He veers on camp and sentiment, from firemen kissing to himself in a hat embellished with a dead Christ. His very few last works, while ill and living with his parents back in California, manage little more than the fantasy, in what might represent plants, space aliens, or nothing at all. The curators, Sergio Bessa and Yasmin Ramírez, include archival photos (although not ceramics), in a show of ninety objects that passes all too quickly. They testify to abandoned and demolished buildings, but the paintings do not. Still, Wong will always have those walls—with all their care, the illusion, the exclusions and inclusions, and the warmth.

Nicole Eisenman ran at the New Museum through June 26, 2016, and at Anton Kern through June 25. Eva Papamargariti and Cally Spooner ran at the museum through June 19, Beatriz Santiago Muñoz through June 12, Andra Ursuta through June 19, and Goshka Macuga through June 26. Martin Wong ran at the Bronx Museum through February 14 and at P.P.O.W. through February 6.