The View from Above

John Haberin New York City

Yvonne Jacquette, Levan Mindiashvili, and William Steiger

Rod Penner, Domingo Milella, and Antonio Murado

After all these years, I should know my way around New York—and then there is the city of Yvonne Jacquette and Levan Mindiashvili. Each painter approaches common ground from an unusual vantage point, from which it can hardly look stranger or more inviting. They suit a city that is always new.

Is it coincidence that one is from Canada and another from the Republic of Georgia? Maybe so, for William Steiger does much the same for Brooklyn and Queens, while Rod Penner brings something of the same eye to crossing America.  They refresh the scene, while insisting on the perils of objectivity or detachment. Domingo Milella and Antonio Murado put the problem of retaining a sense of place in global terms, with work that treats expanding cities, cemeteries, and Northern Romanticism on equal terms. Still, the realities of vision and urban decay have a way of intruding, as if from last worlds.

They refresh the scene, while insisting on the perils of objectivity or detachment. Domingo Milella and Antonio Murado put the problem of retaining a sense of place in global terms, with work that treats expanding cities, cemeteries, and Northern Romanticism on equal terms. Still, the realities of vision and urban decay have a way of intruding, as if from last worlds.

Stone and glass

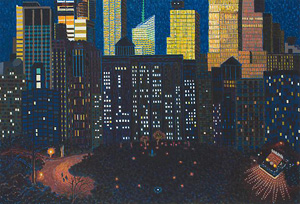

Yvonne Jacquette has a fondness for actual tourist attractions. One should have no trouble recognizing a skyline that includes the Empire State Building and the Chrysler Building, but one might not guess the point of view from Hudson Yards. One may not recognize the Museum of Natural History at all. Seen from across a rooftop and water towers, its castle towers and recent extensions look more like an armory being put to new uses. Jacquette also has a fondness for sites in transition, like the Whitney under construction in the Meatpacking District, with a museum opening in May 2015. Its cranes make decrepit Hudson River piers look like sites of industry.

Above all, she adopts a view from above, one in which trees hide Washington Square in front of NYU's library. Even the High Line looks low. The scattered lights in high-rise windows at night deliver the city's message in an unknown alphabet. And Jacquette's time of day is the nighttime, even in mid-morning or afternoon. Deep blue dominates, its variations standing for river, sky, glass, and shadow. To that add an equally saturated yellow or orange, one that turns the distant outer boroughs into Lego blocks.

She has adopted high vantage points before, and if anything her realism is becoming that much more precise. Works on paper have a denser pattern of pastel, while oil on linen treats drawing more freely. As cars round a bend on West Street, they leave colored arcs both in front and behind, as actual headlights never could. Lanes might be following a geometry of their own imagining. When Jacquette does leave the city, for Maine and beyond, the work becomes far less vivid. Even in New York, something keeps repeating comfort food, but at least she keeps the food warm and the viewer hungry.

Levan Mindiashvili, too, looks to the sky and to the distance. Maybe New York is necessarily remote to an artist from the Republic of Georgia—still living, as the show's title has it, on "Borderlines." He sees it at more than one remove, in reflections off otherwise unseen buildings. The glass imposes a grid all its own, flattening corner points of view. Working in acrylic, oil pencil, and charcoal, Mindiashvili then adds sharp colored lines for traces of sunlight. Old stone can take on the crispness of commercial architecture or jiggle in its ad hoc mirror.

The grid belongs at once to two façades, to the picture plane, and to the viewer. Yet the unfamiliarity is only partly a matter of space. It is also a matter of time. One has the past time of the urban history, the present time of vision, and the future time of painting and architecture under construction. Mindiashvili also leaves portions of the canvas schematic or empty, like blueprints. It is my New York and yours all the same.

The grid belongs at once to two façades, to the picture plane, and to the viewer. Yet the unfamiliarity is only partly a matter of space. It is also a matter of time. One has the past time of the urban history, the present time of vision, and the future time of painting and architecture under construction. Mindiashvili also leaves portions of the canvas schematic or empty, like blueprints. It is my New York and yours all the same.

One could almost dismiss the work as eye candy, but resist. True, Jacquette approaches the city a little like a tourist, without regard for dirty details. Her Whitney stands largely apart from the politics of museum expansions, her Hudson Yards apart from gentrification, and her NYU apart from the impact of its growth on the neighborhood. This is not the gritty waterfront of George Bellows and the Ashcan school, not by any means. Still, painting here, as for Don Eddy and others, can teach one to rediscover the urban landscape. Who knew that the mirror onto nature would be the side of a building?

Out of gas

Photorealism aims for amazement, like Rackstraw Downes on Staten Island or Bradley McCallum in a time of war. One comes ever so close, to see that every detail and every brushstroke is in place. And then it aims for detachment. This is, after all, the realism of a photograph, not another kind of insight, in which paint transforms itself before one's eyes into people, places, and the light. Rod Penner pulls off that peculiar mix of intimacy and distance. And he locates that mix in America.

Penner's America does not have the pop sensibility of Richard Estes or the creepy Neo-Mannerism of Philip Pearlstein. It has plenty of room for parking, as with Robert Bechtle, but not a car in sight. It does not show off, like Chuck Close. Rather, it looks abandoned, to the point that one still hesitates to enter. It has all the familiar monuments to transience—the gas stations, cheap houses, diners, and motels. To reach them, though, one would have to cross a forbidding intersection, a parking lot slippery with ice, a tree's network of branches, or a lawn with the weighted memories of an empty stroller or backyard bench. A sign even states clearly, Do Not Enter.

The landscape has plenty of other signs as well, in an American culture that takes pains to be explicit. One halfway destroyed building holds a glowing neon frame. Mostly, though, Penner bathes his scenes with a strangely uniform light, even during his favorite time of day, sunset. The light brings home another paradox, too, of transience and stillness. The sheer size of his paintings brings out the dilemma of whether to linger or to move on and away. The artist has basically two canvases, small and smaller, and the smaller compositions (six inches on a side) look cropped arbitrarily from something larger.

Rather than the blustery colors of Pop Art, Penner sticks to relatively small strokes and neutral tones. A billboard for fireworks covers the side of a building, and while there are no fireworks, there is a warm mist. The foreground holds all the action, like manhole covers, but not much in the way of detail, such as litter. The cleaning crews must have passed through already as well. The rest lies in the middle ground, with structures duly parallel to the picture plane. Reflections in standing water highlight the hyperrealism as well as the abandonment.

Observing well is the best revenge. Canadian by birth, Penner could still be seeing the country for the first time. He could also be crossing the continent, although the series sticks to Texas hill country and the Southwest. It recalls photography's epics of America, as with Robert Frank and Lee Friedlander as "framed by Joel Coen"—or Emmet Gowin from the air. It also recalls the gas stations and Southern California boulevards from Ed Ruscha, but not as an exhaustive record. It updates their deadpan for an economy out of gas.

William Steiger sees New York from above, as a work of art but also as home. As with T. J. Wilcox on video from his studio above Union Square, it may take time to realize that the city is changing before one's eyes. His style approaches an older American realism, that of Charles Demuth or Ralston Crawford, with a spareness that recalls the gallery's fondness for both Minimalism and abstraction. Yet Precisionism's flat planes and product logos also anticipated Pop Art, to the point that Robert Indiana took Demuth's I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold as his own. Steiger's is the New York of the Silvercup sign on a Long Island City rooftop, the Kentile Floor sign in Brooklyn, and water towers. I took the walkway on a bridge to Manhattan the weekend before, and now I could approach it or a roller-coaster so closely as to become tangled up in its industrial grid. Other artists use the old Silvercup bakeries as film and television studios, but Steiger prefers the vision, the tangle, and the heights.

Landscape with headstones

When Dutch painting first looked at the earth and sky, it saw an independent nation. And when the Hudson River School looked up, it saw a visionary landscape, but also nation coming apart. In each case, landscape told them who they are. Domingo Milella might put that in the past tense: who were these people? His photos cover cemeteries and cities, and only the first look fully alive.

Photography, no doubt, is supposed to provide documentation, of lost worlds or cities in ruins. Then, too, people commission monuments to leave a suitable image behind. And Milella includes a few of their efforts, including the tomb of King Midas in Turkey. Its stone face looks like a house front that refuses guests. In another image, a finely etched inscription vies with deep fissures in stone. The gallery speaks of his subject as "the flux of human civilizations."

Perhaps, but his main series is livelier, because it unfolds fully in the present, with all the sharpness of a large-format camera. From 2004 to 2011, Milella crossed Mexico City, Ankara, Tunisia, Cairo, and his native Italy. He found garbage in a foreground coastline and houses piled on distant hills. They fit awkwardly between tenements and rocks, crossed by artificial lights at night and utility wires by day. They also bear an uncanny resemblance to fields of headstones, except that the latter have a purer white. Both seem long since to have run out of room to accommodate more.

Antonio Murado's vistas look still more inhuman, but then he is paying tribute not to civilizations but to abstraction and to painting. His subject resembles a familiar Romantic landscape, like that of French landscape drawings before him, of infinite distances and dark mists. Up close, its apparent precision melts away, but not its realism. If anything, the landscape looks that much more massive. It also bears an unusual scale marker. The Spanish artist paints an irregular color field at the bottom of each one.

One might expect a closure or an obstacle, like those tombstones. It shares their blankness and then some. In practice, though, it brings the entire scene into focus. The painting appears continuous, for all the sharp edge between realism and abstraction. The implied perspective acquires a foreground, and the near monochrome of blasted forests, mountains, and sky acquires its implied color. The depths settle down to earth, while the color field seems to float.

Landscape has long inspired abstract painting. Robert Rosenblum famously sought the origins of Abstract Expressionism in the Romantic sublime, and floating fields of color are bound to recall Mark Rothko. Murado, though, offers something less transcendent and ethereal. His color fields are closer to Ellsworth Kelly and the texture of his realism, almost like graphite, is closer to early Brice Marden. From Ruysdael to Rosenblum, landscape taught people who they aspired to be. Some artists, though, would rather be grounded.

Yvonne Jacquette ran at D. C. Moore through February 8, 2014, Levan Mindiashvili at Lodge through February 4. Rod Penner ran at Ameringer | McEnery | Yohe through November 23, 2013, William Steiger at Margaret Thatcher Projects through December 14, Domingo Milella at Tracy Williams, Ltd. through December 21, and Antonio Murado at von Lintel through December 7. A related review gives separate attention to Yvonne Jacquette.