4.9.25 — Passing or to Come

In 1924, eleven years after J. P. Morgan’s death, the Morgan Library opened to the public. His son relied on it too little to keep it to himself and respected it far too much. Its outreach has grown ever since, from galleries where Morgan once had his home to the garden where visitors can imagine walking beside him.

It still has the feel of a private treasure that they, too, can call their own. A nook out by cafeteria has children’s books for those too young and too in love with words to prefer high tea. It may have lost its serenity and dedication since Renzo Piano added an atrium, but now another presence walks alongside you as well, Belle da Costa Green.

It still has the feel of a private treasure that they, too, can call their own. A nook out by cafeteria has children’s books for those too young and too in love with words to prefer high tea. It may have lost its serenity and dedication since Renzo Piano added an atrium, but now another presence walks alongside you as well, Belle da Costa Green.

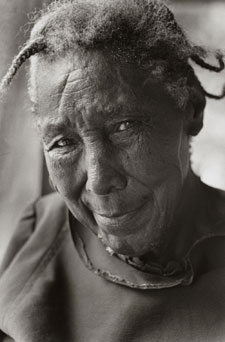

Jack Morgan rehired his father’s personal librarian and appointed the Morgan’s first African American director. Did you know that they were one and the same? If not, you are hardly alone. In her own time, Green passed for white. An exhibition calls her “uncompromising,” but was it a compromise or an act of defiance? For its centennial, the Morgan seeks “A Librarian’s Legacy,” through May 4.

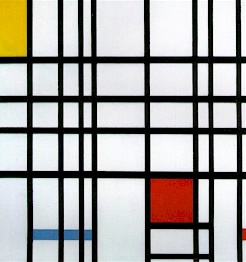

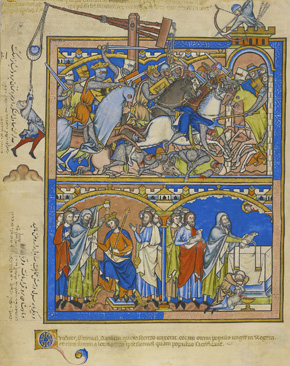

The Morgan’s anniversary celebration began with a display of Morgan’s Bibles and, in delicious counterpoint, Medieval money. And surely anyone who worked so closely with a wealthy man who fashioned himself a scholar had to respect his tastes. And, sure enough, “A Librarian’s Legacy” gives due space to illuminated manuscripts like The Crusader Bible. It shows off not one but two Rembrandt prints, including one long known as The Hundred Guilder Print for its public presence and its cost. Still, she plainly exceeded Morgan’s scholarship and shared his tastes. This was not a compromise but a true collaboration.

How, though, did Belle Marion Greener, a black kid from Washington, D.C., become Belle da Costa Green? And how did she become the librarian of an outstanding collection while still in her twenties? The curators, Philip Palmer and Erica Ciallela, give her both the museum’s most prominent galleries—the first for her story and the second for her work. Born in 1879, she grew up in the north of the city, closer to Howard University, the historically black college, than to the Capitol. Still, her father, headmaster of a segregated school, was the first black graduate of Harvard, and her mother’s family valued class and education as well. They had a society wedding.

On their separation, her mother took her to New York and changed their name. It was a new life, with bustling streets and a picnic up the Hudson. She served as librarian at Princeton before leaving for Morgan in 1905, while its Charles F. McKim building was still underway. Still, it was the age of Jim Crow, public lynchings, and racism that embraced its name. A photo by Alfred Stieglitz shows Jean Toomer, a leader in the Harlem Renaissance who became a Quaker and left for rural Pennsylvania. Passing, it seems, is what you make of it.

Greene made the most of it, and the press found her irresistible for her achievement, good looks, and fashionable comportment. So did such photographers as Charles White, who shows her profile, her head duly raised. When she lets her guard down for a smoke, that was a pose, too. The show’s second half centers on her imposing desk, but she did not sit still. She took her expertise and selections from the Morgan to New York’s Public Library and the 1939 World’s Fair. She oversaw conservation of a work after Botticelli that hung and still hangs among lesser Renaissance paintings in Morgan’s study.

Just what, though, did she contribute? The show has plenty of evidence, including ledgers and a library card, but few answers. Past shows have slighted her in favor of Morgan and present-day curators, but still she has her range, from the Middle Ages to twentieth-century work that her patron might never have swallowed. She thanked Abraham Walkowitz personally for his 1913 Human Abstract. And, in her own less than obvious way, she had her race. Years before, her father had appeared with Frederick Douglass in a print of leading black Americans, and one of her last acquisitions was a letter from Douglass, before her death in 1950.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.