4.25.25 — Distant Companions

Caspar David Friedrich would never be alone as long as he could journey to the forest and the sea. They were all the company he needed, their bare trunks gathering the darkness in winter, their foamy crests the turmoil in his soul. When he faces waters and distant hills, there is literally no looking back.

He could have found his double in many another painting as well—or in the companions his doubles took with them to catch the rising moon. In 2001, the Met had a focus exhibition on Friedrich’s Moonwatchers (in the plural),  not its last show of German Romanticism, and I excerpted my reviews of both just this week for you. Rather than start over, then, let me turn briefly to an ample retrospective, again at the Met, through May 11.

not its last show of German Romanticism, and I excerpted my reviews of both just this week for you. Rather than start over, then, let me turn briefly to an ample retrospective, again at the Met, through May 11.

Friedrich will never be at a loss for company, but it will never be enough. The men here are anonymous, not the celebrated poet and painter doubling and redoubling the very notion of Kindred Spirits for Asher Durand in America, in 1849. Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog , dressed in black and hand on one hip, faces down what he sees, apart and alone, even as his gaze reaches out to infinity. The earth replies with the chilliest of white and uniformly cool colors. Where many a Romantic captures motion and the light, gestures and colors here are barely natural. And their dangerous infinite makes this the Romantic sublime.

Friedrich belongs to a long tradition in German art, going back to pale flesh and moist flowers in late Renaissance nudes and Baroque still life. Friedrich took nature as his subject, but not as a naturalist. Unlike John Constable or Beatrix Potter, he left few quick studies of clouds or botanical species. Like a proper student, he built a reputation in drawing before he even approached painting. The Met opens with local scenery and familiar faces in works on paper, including his a self-portrait. Only then could he test the limits of observation and human understanding.

As curators, Alison Hokanson and Joanna Sheers Seidenstein make a point of that slippery contrast between the visible and the infinite, the known and the unknowable. For Friedrich, it is also a struggle for the meaning of vision, between the seen and the imagined. And the imagination wins out. A cross set again and again on a rock in early work, much like the wanderer’s tall crag, looks out on a full moon. Sands at sunset become the stage for an allegory of the stages of life.

But what is imagined and what lies just next door? What of a the portal of a church or the western façade of a cathedral? What of an equally grand stone arch? Friedrich keeps you guessing. Facing each, one can feel the same ever-present chill. The show proceeds chronologically and by motif, but Friedrich found his subject and style early on, apart from mistier early skies and the more explicit Christianity, and never let go. So, too, did fellow Romantics like Johan Christian Dahl and Carl Gustav Carus, and their works, a handful also on view, are hard to distinguish from his. For all his virtues, sameness means predictability.

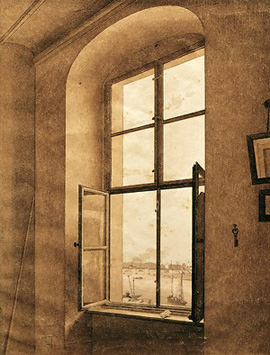

The familiar experience has made him a crowd pleaser. Who can resist warm associations and stark feelings? Who can resist knowing what to expect? Still, Friedrich darkens and colors both brighten and deepen in late work, as if the foreground were itself layered over the whole. His studio window becomes as prominent as what he found on the other side of the glass. The infinite begins with the picture plane and with you.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.