Boundaries to Abstraction

John Haberin New York City

Merrill Wagner and Thornton Willis

You may walk right past a series of photographs on the way to Merrill Wagner and her paintings. You will have other things on your mind, but watch out: you will have crossed a fence. It makes sense if you think of abstraction as about regular geometries and breaking boundaries.

For Wagner, art is also a human intervention in a not so natural landscape. When she photographs fences from day to day (published as A Calendar), she is taking stock of herself as well. Even when she sticks to painting, she is marking time and space. Now in her eighties, she was already in a great tradition of postwar American art. It allowed her to use abstraction to stay literally in touch with the earth and the light. Meanwhile Thornton Willis uses his long commitment to abstraction not to abandon its logic or complexity, but to pare back the better to reveal both.

Good fences

Inside at the New York Studio School, Merrill Wagner has more than forty years of work, from pencil sketches to a field of blue the size of a wall. It only gains in intensity from swirls of bright pastel, oil pastel, and graphite across its three panels. More somber tones and more reflective surfaces lean against or spill off other walls. Even from that narrow entryway, one can see a circle of stones on the floor, each touched by a circle in acrylic. A crusty green mass of stone rests nearby, as if it had erupted on the spot. Painting has taken on color, weight, and material presence.

With all that ahead, it is easy to miss the photos across from the guest book. Just be aware that, in entering, you will have crossed that fence. More precisely, you will have crossed sixteen fences, set in four rows like postcards or a scrapbook. The camera captures them more or less head-on, beneath nearly blank skies and behind a small patch of water or earth. Ripples in the water and the rough surface of soil and stone interact with light, much like Wagner's paintings. You can see why their titles, too, so often refer to landscape.

The photos date from 1982, when she was in the habit of painting squares or rectangles on a fence and returning to watch them fade in the face of time and weather. Yet they also call attention to the fences. Each barrier marks off its surroundings, summons them into view, and subjects itself to their changes. It parallels abstract painting as a response to natural light for Agnes Martin—much as the pencil sketches, from 1971, parallel Martin's early grids. It has a parallel in earthworks from those years as well, without having to move so much as a shovelful of earth. One can see why Wagner called a book Time and Materials.

They also make a good frame for the work inside. They have a striking resemblance to strips of yellow masking tape from 1975—with portents of such younger artists at the Studio School as Medrie MacPhee and David Humphrey coming up. As work sites, they also correspond to Wagner's turn to scraps of natural and commercial materials. Not that she necessarily distinguishes the two. The large blue painting, Meander from 1980, covers Masonite treated with slate. Red scrawls meet a small slab of marble.

One painting even salvages a screen, the kind for fencing. The bulk, though, since around 1990 consists of rust-resistant paint on steel. These are not shaped canvases, but they do use their materials to shape a painting. They apply close shades of gray and yellow or the contrast of purple, gray, and blue, as studies in light and texture. They recall metal panels in earthshaking white painting by Robert Ryman, Wagner's husband, and I dare not ask who influenced whom when. Then, too, Cordy Ryman, their son, paints on wood very much like fence posts.

Born in 1935, Wagner arrived in New York in 1957 and took to geometry in the 1960s—although the show picks her up only in 1970s, just as she and Pat Adams were coming into their own. The curators, Cordy with Hanne Tierney of Brooklyn's FiveMyles gallery, do not have the space or resources for a fuller retrospective, but they do a terrific job with two rooms. Critics often spot her connection to landscape, speaking of plein-air painting or the sublime. Still, these are human interventions, like rust-resistant paint, working against time and change without being able to keep them quite at bay. Wagner calls one painting Outerbridge Crossing, which sounds like a creek in a remote wild, but names instead the southernmost bridge from Staten Island to industrial New Jersey. For New Yorkers, that still counts as the wilderness, and maybe it does, too, for art.

Beyond the fences

Wagner had a secret weapon in her paintings from the 1970s, their support, and if it is hard to keep a painting's physical presence secret, that is precisely the point. Many make use of tape on Plexiglas. Another distances canvas from a stretcher to find new support, in the walls and floor, where three dark squares mark out a corner of the room. Like much of the tape and her brushwork, the squares have ragged edges, just in case one was tempted to overlook their presence. And it is tempting, just as one can write off Ryman as the painter of white on white—forgetting his range of materials from canvas and metal plates to the bolts holding them to the wall. For both artists, it takes looking at what lies right before one's eyes.

The New York Studio School makes the background to painting inescapable. Its show spans her career, including work from the 1980s on several panels—somewhere between painting, sculpture, and relief. It also includes those photos of fences in the New York metropolitan area, not so far from the verticals of cloth or masking tape. A gallery show six months later hones in instead on a crucial decade, when she turned thirty, making them together a fairer retrospective. It shows her as, first and foremost, a painter. No wonder it takes looking.

Wagner does not appear in "Making Space," a survey of women in abstraction, but she could have appeared if only MoMA had taken more care to collect her. (She did appear there that very decade in a Christmas show.) She, too, is making and marking space, in line with the period's emphasis on art as object. The verticals have their parallel, so to speak, in stripes by Frank Stella, the dark squares in Ad Reinhardt. A red square, for that matter, deepens into black. Even her forays out of doors have a parallel in the economy of plant studies in sketches by Ellsworth Kelly, back in Chelsea a door away from his last paintings.

For all that, she has little of their austerity—precisely what can tempt one to see only painting. One can come up close to watch the red vary and deepen, rather than wait for it to pop out of a near uniform blackness. One can stand back to compare its dimensions, brushwork, and tape marks with other colors set against uniform squares of Plexiglas. Not that they form a single work or even a series, but creative hanging invites a closer look. Paired yellow verticals look worn by earth or fire, while other works stick to competing fields and tones of black and gray. The show's largest canvas stands alone, and its broader verticals dissolve at the edges like horizontal bands for Agnes Martin.

She is also not above illusion, as long as it can coincide with the literal. The corner piece looks at first like a translucent black cube, before falling back to canvas. It matters, though, that it still looks solid and painterly as loose fabric. It matters, too, that the weathering in earth tones on yellow depends on a combination of chance and her own hand. While other artists use tape to give geometry its clean edges before peeling it away, she uses it to mess things up. Where the fences make one aware of all her work as making space, here she is marking time.

Jill Moser marks time in abstraction, too, with a record of her art's making. Twenty years younger than Wagner, she survived a long stretch of silkscreens and appropriation, when painting was out of fashion. She incorporates them into her work at that, along with oil on canvas. She, though, is appropriating only herself, in what can pass for just painting. Thin drips and curves contrast with underlying broader patches—and the opacity of the first with the translucency of the second, like passing showers in front of clouds. Together, they offer at least two versions of the definite or the ephemeral.

Floating back

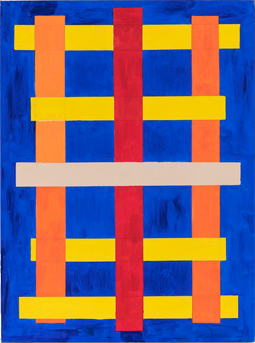

I hate to argue, but Thornton Willis has it wrong. He calls his latest paintings "Floating Lattices," but it is not the lattices that float. More remarkably, it is paint itself. Not that the lattice is any less clear and any less responsible. Willis has pared abstraction down to basics, in order to mess things up once again. He could not have made paint float any other way.

I hate to argue, because Willis has earned the right to say what he likes, in painting and in words. He has been exhibiting since the 1960s, when geometry ruled, from Minimalism in three dimensions to Frank Stella and William T. Williams in stripes, and he is still at it. At age eighty-six, he calls this show the "launch" of a new series. One can only hope for more. Still, he is easy to take for granted, and I have mentioned him before only hastily. This new beginning should, finally, have one looking back.

I hate to argue, because Willis has earned the right to say what he likes, in painting and in words. He has been exhibiting since the 1960s, when geometry ruled, from Minimalism in three dimensions to Frank Stella and William T. Williams in stripes, and he is still at it. At age eighty-six, he calls this show the "launch" of a new series. One can only hope for more. Still, he is easy to take for granted, and I have mentioned him before only hastily. This new beginning should, finally, have one looking back.

The lattice is the easy part. Three broad verticals never touch the edges of a tall canvas, crossed by up to five more. Each has a single color, at least apart from the crossings, and all fall more or less neatly within ROYGBIV. Each, too, could pass for a single stroke from a broad brush or even a cutout. Look more closely, though, and the strips or stripes show clear signs of protracted brushwork, so that the color of a crossing stroke may or may not show through. The appearance of collage derives from thick, firm brushstrokes as well. First efforts allowed a fourth vertical, rougher edges, and additional colors within a stripe, but Willis really is paring back.

In retrospect, he has been doing so all along, in a call and response to his own self-evidence and simplicity. An earlier series had off-center trapezoids amenable to painting with a roller, but he may have come to find the asymmetry hard to justify and the caked background distracting. He responded with short red stripes, each at right angles to the next and set against black, but their stepwise descent may have felt arbitrary, too. So he pruned back to squares and rectangles, filling a painting with lighter colors more suggestive of the unseen ground. This, it must have seemed, is what geometric abstraction is supposed to mean, but the shapes sure ran every which way. They were all the more eye-catching for that, but did painting have to be so busy, he must have asked?

And so the lattice, but here, too, things get complicated. For once, Willis leaves open the possibility of illusion. The background becomes a field in space, while its light or dark blue plays a role in the composition as well. When stripes cross, they appear to go over or under each other, and successive horizontals may go first over and then under the same vertical. That is what makes this a lattice. Just as much, it grounds a lattice in the picture plane while carrying it forward into the viewer's face.

The whole story of Minimalism, not to mention a kind of neo-Minimalism in younger artists today, lies in that back and forth of simplicity and messing things up. Think all the way back to Ad Reinhardt, where black can contain all sorts of color. The only difference is how much Willis stays grounded. He has the exact opposite trajectory from Stella's, toward stripe paintings rather than away. Sometimes the crossings, which are necessarily squares, are coarse gray, like the product of subtractive color. Where other artists have their color charts, color lines, and color wheels, he has his color lattice, and its color floats.

Merrill Wagner ran at the New York Studio School through January 8, 2017, and at Zürcher through June 24, Ellsworth Kelly at Matthew Marks through June 24, and Jill Moser at Lennon, Weinberg through June 17. Thornton Willis ran at Elizabeth Harris through April 8, 2023.