7.17.24 — Flattening Edo

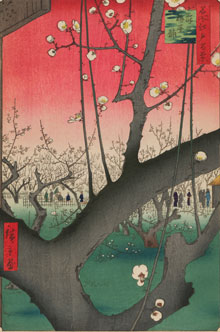

To wrap up from last time on 100 Famous Views of Edo, I began with the changing city, because the museum does. The curator, Joan Cummins, makes a point of it, with wall text and a map, rather than changing colors, line, and light.

Despite herself, though, she sticks to tradition. An opening room introduces Hiroshige and pairs one print apiece by him and Shigemasa, but then the show moves on. (The older artist has a scratchier line, greater detail, less poetry and humor, and little color.) It saves Takashi Murakami for last.

Despite herself, though, she sticks to tradition. An opening room introduces Hiroshige and pairs one print apiece by him and Shigemasa, but then the show moves on. (The older artist has a scratchier line, greater detail, less poetry and humor, and little color.) It saves Takashi Murakami for last.

Separate rooms for the two principal artists do not interrupt the flow of a series. It is up to you to compare and to contrast. Still, a small room between the two brings Tokyo into the present. In photographs by Alex Falcón Bieno, shops have become skyscrapers, and an elevated train follows the curve of a street. They look familiar from Hiroshige all the same. He is still the traditionalist and the visionary.

Had he visited the West, he would have had adjustments to make, ever the urban explorer. I can imagine him in Paris, heading up the Seine with Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir to be sure that he had seen it all—and that brings one to Takashi Murakami. He speaks of Renoir and Vincent van Gogh as influences. Does he really need to reach Hiroshige by way of Paris, and can he? A more obvious influence is Pop Art. Surprisingly, it may add to his respect for the past.

Perhaps it must, if you associate Pop Art with Andy Warhol and quotation. And Murakami takes quotation seriously. So much for the originality of the avant-garde. I kept waiting for modern Japan or Mickey Mouse to drop into his “famous views,” but they never do. You may struggle to figure out what, if anything, has changed between one series and the next. But then, if Warhol is right, what can change?

For one thing, painted views have become larger, and the series in full fills its single wall in three tight rows. At the same time, they have become flatter, as has to happen in blowing them up to poster size. They look all the brighter for that. They also call attention to the older artist’s attachment to the picture plane. Did Hiroshige allow a tree branch to loop over itself? With Murakami, the closed loop is that much harder to miss.

The flatter colors echo Pop Art, of course, along with the current fashion for anime and cartoons. The sheer pace of his work may make him sound glib, and so he is. There is nothing like Hiroshige for his stillness and humor. Will Murakami’s Edo ever be a famous view? Can quotation alone serve for the vitality of a changing city? Should Hiroshige vanish again for another twenty-four years, for preservation, it may have to do.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.