Fabric and Heavy Metal

John Haberin New York City

Lynda Benglis and Lee Bontecou

Art seems to flow from Lynda Benglis, like her latex of the late 1960s, in color quite literally poured out on the floor. By now one can take her presence for granted—or rather two presences, and only one is her sculpture. It still flows, although since the 1970s it has looked much more obviously like art. It has swept up high on the wall, like knotted fabric but in spray paint and plaster. It has swelled up from the floor, as if out of a volcano, and appeared as utter schlock, as gilded fountains. I have seen kids treat her sculpture like playground equipment.

In other words, her art is as feminine, elegant, and confrontational as her other presence—a notorious nude ad she placed in Artforum nearly forty years ago. Women often object at having to choose among adjectives like these, for good reason.  If women artists make just "woman's work," they take second place to men. If they play hardball, they come off as pushy, where men would come off as strong—or as the latest thing. Parallel complaints nag at women in politics, the workplace, and pretty much everywhere else. Any minority will know the conundrum, except that women outnumber men.

If women artists make just "woman's work," they take second place to men. If they play hardball, they come off as pushy, where men would come off as strong—or as the latest thing. Parallel complaints nag at women in politics, the workplace, and pretty much everywhere else. Any minority will know the conundrum, except that women outnumber men.

Benglis has an edge, however. As both artist and provocation, she takes on the adjectives without losing a step. Since the conundrum involves the connection between power and self-representation, no wonder a good artist can explore it. Both her gallery and now the New Museum have explored it, years apart, with attempts at retrospectives. So does a retrospective of Lee Bontecou, who took a blowtorch to art. Each puts art by women in focus while competing on allegedly male territory, themselves.

Cockiness erupting

A purported gallery retrospective of Lynda Benglis looked curiously small and familiar. So, in fact, does her museum retrospective seven years later. The latter expands her canon to video, but includes barely fifty works. Yet both shows help make sense of two almost shockingly different views of the artist. How dreadful to be so creative that, in retrospect, one becomes simply part of one's time. And she was, but oddly enough one remembers two very disparate images of her time.

One was so singular that who could care outside Soho? There she was, in the ad that she placed in the cutting-edge arts magazine in 1974, fondling a big dildo. She wore only sunglasses, a real or artificial tan, hair plastered down like a dark bathing cap, and a nasty smile. It caused an outrage that I have trouble understanding this long after. Imagine how some shock art today may look in, oh, six more months. Maybe that explains why she has to share the New Museum with George Condo.

Conversely, one remembers her sculpture as the opposite side of the 1980s. The decade started not just the politics of art-world celebrity, but also the beginning of the end of dogma in art. Benglis has also shared her gallery with Louise Bourgeois, as two "bad girls" in art. Both cast Minimalism aside for "expression" and even "decoration." They fit nicely in one's historical memory with Joel Shapiro and his public sculpture, Elizabeth Murray and Murray drawings, or Frank Stella and his metal relief paintings, just for starters. The new had become neo, without most artists even noticing.

Unlike traditional sculpture, Benglis's work often hangs on the wall. Her bows, knots, and delicate folds painted in gaudy, metallic shades flaunt associations with such "feminine" media as fabric quite as much as Lynn Umlauf in abstract painting. Betty Woodman sometimes does the same with ceramics that invoke classical friezes. When Pablo Picasso stuck a guitar on the wall, in deliberately fragile cardboard, studio visitors puzzled over whether to call it painting or sculpture. (He called it just a guitar.) Benglis demands the solidity of sculpture.

Her knots of plaster and spray paint high on the wall, like her spindles of gold leaf rising from the floor, combine the freedom of fabric with the classicism of a dancer. Her wall sculpture could stand for a frieze from ancient cities—or a fashion runway. The late 1980s added swirls of copper and bronze. They intensify the contrast between the visual richness of painting and the mass of sculpture. Then again, a skirt can mean either fashion or machinery, while a frieze can mean either architecture or woolen cloth. One can still choose which presence to remember, the artist or the bad girl, almost too polite or too provocative.

They may also seem to have little to do with her ad, as if her press agent had handled that for her. Yet each retrospective has proved a revelation. So did an earlier exhibition at her gallery, in 1998, of large work away from the wall, competing for space with the room. They all emphasize a side of her as comfortable with postmodern installations as with sculpture. They are also as assertively and confusingly sexual as her ad. How could I ever have taken her for granted?

Formalism and fashion

The New Museum includes both of Benglis's presences. On the one hand, it keeps the two stories separate. It pretty much quits more than thirty years ago, beyond some darker work in the lobby cafeteria, as if leaving it to her gallery to supply more. It leaves overt nudity to the corridor behind the elevators, separated at one end by a dark curtain as if to protect minors. Along with the ad and other artifacts, it has her video of two women kissing. Meanwhile two large rooms to the front leave ample space for her art.

One the other hand, it connects the stories. It does so literally, with a room to each side. And it does so implicitly, by giving each presence a history. One side room recreates Primary Structures, named for a legendary exhibition of Minimalism a decade before. The 1975 installation at Paula Cooper included fabric, artificial trees, and broken pedestals. The title derives from a 1966 show at the Jewish Museum, curated by Kynaston McShine shortly before his departure for MoMA and featuring the likes of Donald Judd. McShine had defined a late modern canon, just when Benglis and others were about to leave it in ruins—and to populate it with simulated growth and fabric.

The other side room supplies the curtains. It has a spooky row of five green phantoms, the only surviving examples of her 1971 series in phosphorescent foam. They descend from wall to floor, standing out against both and against the darkness. Each side room shows the transition from painting to sculpture. Each also marks the transition from Minimalism's deductive logic to a kind of theater. Each also combines personal imagery and provocation.

The history in the museum's two front rooms helps as well. Benglis, born in 1941, headed north from Louisiana as a painter. One can think of the poured latex as a response to both painting and Minimalism. Where Jackson Pollock worked on the floor, this work stays on the floor. And where Carl Andre neatly tiled the floor, she spills all over it—in a wild mix of blue, red, orange, and green. Darker work was still to come.

Soon the blob fills a room's corner with Quartered Meteor of in 1969—in, not incidentally, Minimalism's heavy metal.  Then comes the discovery of a wire frame beneath the glow of Phantom. It brings support for work on the wall. Materials from glitter and acrylic to wax, lead, and polyurethane have kept Benglis going ever since. The sooty pieces lining the cafeteria add more variations. They also evoke for me Bontecou's blowtorch.

Then comes the discovery of a wire frame beneath the glow of Phantom. It brings support for work on the wall. Materials from glitter and acrylic to wax, lead, and polyurethane have kept Benglis going ever since. The sooty pieces lining the cafeteria add more variations. They also evoke for me Bontecou's blowtorch.

The back room in Benglis's gallery retrospective held more work from her past, mixing classicism and postmodern extravagance. Her gilded plaster ripples along the wall, without ever trying to float free. Rather, it takes weight from the dance, like the figure that might once have worn so glorious a fabric. As Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe says in a fine 2004 catalog essay, surface gives her sculpture mass, just as it did for abstract painting once upon a time. Sure, she can get repetitive, not to mention tacky, but why not? Maybe that keeps her hip.

Post-Minimal or postfeminist?

The 1998 show brought her further, to the end of a century. More often than not, her work there was literally off the wall. This sculpture does not stand to the side while viewers nod off—or maybe fight back. Figures step down from their display, in small maquettes and two big floor pieces. Plaster, painted in gaudy colors, takes on more weight. The paint and wider shapes extend what had been surface to a literal enclosure.

As I watched, two kids tried to crawl under one, and for a moment the skin had become theirs. Benglis's implied clothing had come down off the racks and into a world of bare, human needs. It carries on her old-fashioned play with mass and color. It has the formal variety and everyday materials of canvas and wire by Richard Tuttle, but it never simply falls to the earth. It also makes her theatrical side that much more obvious. The fashion runway has become a stage on which children play.

Maybe I can finally get over the twin stories. Titles like Eat Meat slip easily between comfort and threat, just as meat can be comfort food as well as a vegetarian's nightmare. Something nasty may emerge from Cocoon. This work involves at once nature, the artist, and the viewer, but it has to represent them first. Like drama, it depends on fictions. It gives them a wall display, a stage, and a history.

The ad's feminism points both ways, too. It shows a woman, but a woman in your face. And, sure enough, her layered floor pieces, like molten lava frozen into place, do the same, like the collision between architecture and the human body for Lygia Clark. They, too, suggest the paradox of an artist ready to accept liquid, flowing compositions but also grunge, as if the lava still represent an eruption—or perhaps the product of what that dildo represents. They cast a fresh light on the wall pieces that share the room. Her career's solidity and classicism looks as assertive now as its feminine imagery.

Feminist historians of art are used to competing presences. They must give due recognition to women whose achievement have been overlooked, like Bontecou. But they must also point out the obstacles to achievement. They must refuse to be seen solely as women, while insisting on perspectives that differences may bring. They must probe whether the differences come defined for them by men or by nature, while showing how every definition is an act of description and creation. They must refuse to be defined solely by men, while acknowledging how self-definitions, too, can perpetuate old roles and old biases.

The Artforum ad has been celebrated as feminist and attacked as cruel to women, but one can also credit it as postfeminist. It looks ahead both to self-exaggeration by Paul McCarthy and self-creation by Cindy Sherman. Benglis also helped create post-Minimalism, and her intimate connection between surface and object was a tenet of formalism all along. The deep pleats in copper echo both fabric and heavy machinery, beauty and grunge, and Benglis is quite at home with both. They break down the formal boundary between painting on the wall and sculpture, and they dare to look formal, iconic, and even pretty. Looking back at the X-rated section at the New Museum, one might connect a U-shaped double dildo to the knots.

Soot and gunpowder

If Benglis or Lee Lozano taunts those who would categorize her as a women artist, Lee Bontecou simply dismisses the question. Yet she typifies the enigma of gender roles just as much—or more. I think of her as denying the purity of the female body and its identification with nature rather than neglecting it altogether. She has taking command of the first industrial revolution and is working on the second. She also offered one last pressing reason to visit Long Island City in 2004, before MoMA reopens in Manhattan and MoMA QNS fades into memory. She brought global feminism to the city's most multicultural borough.

If one takes Benglis for granted, Bontecou has made a point of vanishing. Born in 1931 and once the sole woman on Leo Castelli's roster, she stopped displaying but continued her teaching and her art. A Soho loft dweller before that meant anything, she departed for a farm. A pioneer along with Eva Hesse and her Expanded Expansion of materials at once loose, tactile, fragile, and menacing, she offered a model for feminist art while refusing to let the images be written off as a woman's work. Bontecou began with abstract drawings in black and black that may recall the delicacy and rigor of Agnes Martin. They look like pencil but burn like fire.

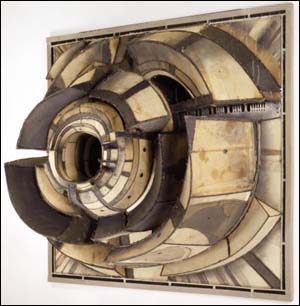

Her signature pieces, like Benglis's, extend and undermine the wall as much as hang on it. They thrust forward several feet. They also surround central cavities that burrow deep into the space of the gallery—not to mention the space of the unconscious. They look at once industrial and organic, until one recognizes the seams as common wire, the terra-cotta hues as torn canvas, and the black space behind as velvet. If that suggests Goth fad, they stay way too grown-up for Metallica fans. They project struggles, shocks, and beauty without the stereotypes.

After a few shaped like broken TV sets—and with about the same functionality—she found her trademark construction of concentric arcs. Bontecou knew that she worked with the same hybrids of machine parts and art supplies as any number of artists navigating "Cubes and Anarchy" after David Smith, whose work was more likely to stand erect. Their subtle twist on sexuality and sensation makes a perfect antidote to model skyscrapers then also at MoMA QNS. Some whirl outward. One has black, steel teeth deep inside. They shy away, however, from the glib association with a vagina, dentata or otherwise.

Her later work has the same confusion of nature and culture. Translucent fish and flowers revel in the tackiness of salmon-colored plastic. Still later, more chaotic works, suspended from the ceiling, look vaguely like a cross between galaxies and something in need of vacuuming up. They leave the wall for good, but they never gain the mass or envelop the space of the cavities. Both series can approach tchotchkes. I can picture the fish in the window of a craft store, shopping-mall variety, and I could definitely live without the gilded fountains.

Still, they help place Bontecou's explorations in a larger arc. They show her always pursuing the mass produced and the handmade, the appropriated and the constructed, the human and the industrial, the late modern and the directions that art is again beginning to follow. Where Jacob Kassay applies charred silver, she applied soot—at times with that blowtorch. Soft textures and holistic imagery may suggest a gently feminine take on Mark Rothko's sublime. Like Benglis, she is too busy to transcend time. Maybe more artists should take out an ad.

Lynda Benglis ran at Cheim & Read through April 3, 2004, where I had also seen her in fall 1998, and at the New Museum through June 19, 2011. The fountains turned up at Salon 94 Freeman, though Marh 11, 2011. Lee Bontecou ran at MoMA QNS through September 27, 2004.