Casting Their Nets

John Haberin New York City

Gego (Gertrud Goldschmidt) and Ruth Asawa

Was the greatest Latin American artist of the last century a German Jew? Better yet, was that artist a woman?

Gego, it turns out, was Gertrud Goldschmidt from Hamburg, and she came to Caracas with no special love for Venezuela or South American culture. Nowhere else would take her. Back when the United States was turning away boatloads fleeing from the Nazis, she was grateful to survive. Yet she thrived, and she set a new model for abstract art in little more than nets and knots, now at the Guggenheim. She did not act alone either, and she had no thought of perpetuating the dominance of Europe. Her catchy adopted name attaches to some deceptively simple sculpture.

This has been a good year for sculpture as a high-wire act, but Ruth Asawa had a way of bringing it back to earth. Like Gego, she worked most often in wire—suggestive of the modernist impulse to reconceive sculpture as "drawing in space." Yet she could not stop drawing everything that she saw in every medium that she touched, from what she called "potato prints" to a bentwood chair in felt tip and ink. Now the Whitney devotes an exhibition to nothing but drawing, as "Through Line." The title could refer to her approach to sculpture, but influence ran both ways. It took sculpture into lightness and drawing into mass.

Like Gego, she worked outside the mainstream, the first in Venezuela and Asawa in San Francisco. One could almost blame Bay Area art for her obsessive touch. Both, too, were displaced by World War II, Gego as a German Jew and Asawa in the internment of Japanese Americans. She must have felt a return to art as a return to freedom, and she later attended a bastion of breaking bounds, Black Mountain College in North Carolina. Still, she kept her eye on detail, like fish scales, the pores in a cork, or the veins and outlines of a leaf. She cared way too much to let go.

A knotty problem

As a refugee in the century's darkest hours, Gego has a familiar history. Abstract Expressionism had, no doubt, its "real Americans," like Jackson Pollock from Cody, Wyoming, with his muscular build, delicate psyche, and delicate but muscular painting. Yet his art took off from Surrealism, and he broke through only after studies with Hans Hofmann from Germany. It was a movement of refugees at that, starting with Arshile Gorky after the Armenian genocide. A postmodern critique, by Serge Guilbaut, asks how New York "stole the idea of modern art." It might better ask how Europe tossed modern artists in the trash and threw modern art to New York.

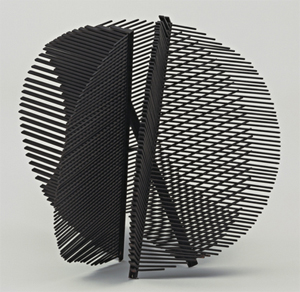

Gego has a familiar art as well, and it deserves to be better known. She adopted welded steel in 1959, like Americans from David Smith to Alexander Calder. Her slim parallels have their echoes as well in Europeans like Alberto Giacometti with his fragile human forms and Women of Venice, Marcel Duchamp with his bicycle wheel, and Julio González in Spain. They appear first as the parallel cuts in engravings, akin to the thin lines and soft edges of Paul Klee in paint, and as sculpture they change as one walks past them, like Op Art. A title spoke of Dynamic Movement. As sculpture, they anticipate what New Yorkers were about to call "drawing in space."

Within a decade, drawing and space become explicit. Parallel lines become separate lines, or Líneas Separades, and solid rods give way to wire, held together not by welding, but by handmade knots. The Guggenheim's tall gallery just off the rotunda introduces their variety. Constructions range from spheres to square pillars like paper lanterns. They may lie about on the floor or hang from the ceiling. They tumble into one another as well.

Gego spoke of seeking not volume but mass, but it could just as well be the other way around. She called many a series Reticulárea, meaning reticular or net-like, and these are nets to catch space. By the 1970s she could speak of steel tapestry, and they look ahead to the revival of tapestry and hangings in art today. If they still have mass, air itself could weigh them down. Like Senga Nengudi with fabric covering rocks or her own body, she could play space against mass and seeming material against physical material. Sculpture bears weight but retains its lightness.

Gego cast her nets widely. She may not refer directly to craft or local tradition, but she remade abstract sculpture as line along with others. Like Lygia Clark, Hélio Oiticica, Mira Schendel, and Jésus Rafael Soto, she could claim modern art for herself while offering an alternative in the new world. Could that alternative have an inspiration in South American earth? Other late series include Esferas, or spheres, but also Troncos, or tree trunks, and Chorros, or waterfalls and streams. She lived outside Caracas for some time, nearer the seacoast, and it impressed her deeply.

An early watercolor shows a cloudy sky, far from the very different storm in Germany. She may have the sky in mind, too, when she adopts the greater transparency of wire grids. She is still after what she called "drawings without paper." A square net could almost pass for folded paper itself, its pleats catching the light. One work in rods consists of loosely stacked squares, like tumbling dice. What hangs from the ceiling may yet fall to earth.

The refugee in Latin America

The curators, Julieta González of the Instituto Inhotim in Brazil with the Guggenheim's Geaninne Gutiérrez-Guimarães, and Pablo León de la Barra, call the retrospective "Measuring Infinity." They make room for some two hundred works. It is a lot to take in, on all but the top floor of the Guggenheim's ramp. (It flows naturally into a chaos of found objects from Sarah Sze.) Still, it divides neatly between two bodies of work, the rods and the mesh. But is it Latin American art?

One could make the case either way. One story would speak of a global tragedy—and the final triumph of a lifelong exile. Some of Gego's relatives found sanctuary in England, and she herself made it to Venezuela barely in time, in 1939. And then came the massive repression of a postwar regime. Still, she found a receptive audience, as a teacher and artist. She also found a cushy home and studio in Caracas, her "Penthouse B."

The other story would speak of a born collaborator. No wonder she could collaborate in the creation of a new Latin American art. Born in 1917, she came of age when the Bauhaus encouraged artists to take design seriously and to market themselves as well. Trained as an architect, she designed furniture. Gego became her brand name, and she worked with graphic designers to turn it into a logo. The Guggenheim displays several versions and adopts one as a logo for the show.

It takes both stories to make her case. Her development looks seamless, but development it was. The show moves rapidly from the outsize pleasure of the two-level gallery to the first sketches and prints, as a kind of explanation. It moves just as quickly from the rods to the mesh. They seem of a piece on one's way up, but the rods look heavier and less effective on one's way back down. They are the early Modernism that she left behind.

Had she left Europe behind as well? Gego recasts Modernism itself as an art of Latin America and an art of refugees. The museum includes nothing at all from before her departure for Caracas, but she needed a fresh start. (It makes little effort to account for the years from 1939 to 1959 as well.) She exhibited on late trips to New York and Frankfurt, but she was looking beyond both. The nets really do cast more widely.

Curators these day make a point of cultural identity and indigenous arts. Just maybe, though, purity was never the point, and neither was pride apart from sorrow. No wonder some artists have sought their roots in Africa or the Caribbean while affirming their love of Western art. No wonder, too, that a German Jew, a non-practicing one at that, could come to typify South American art. She could never forget the fragility of art and life, but she could look ahead. She died in 1994 at age eighty-two.

High-wire act

Wire can come as an airy rebuke to the unbroken welded steel of sculptors from David Smith and Alexander Calder to Mark di Suvero, Tom Doyle, and Joel Shapiro. An artist simply tied her wire to hold it together. Still, sculpture for Gego can also serve as a model for architecture in 3D and in mass.  For Ruth Asawa, sculpture emulates the human form, with bulges like hips. It also has an inhuman vertical symmetry, bringing it closer to abstraction. So does folded paper between drawing and sculpture.

For Ruth Asawa, sculpture emulates the human form, with bulges like hips. It also has an inhuman vertical symmetry, bringing it closer to abstraction. So does folded paper between drawing and sculpture.

Born in 1926, Asawa grew up on a family farm in California, near dirt roads that already must have taught her to look down. Black Mountain College encouraged her interest in origami, but her teachers had higher aspirations. She studied math with Max Dehn and a vision of the future with Buckminster Fuller. She patterned receding circles after Merce Cunningham in dance. A 1989 video shows her still learning from movement as plain as breathing. Most of all, she said, Josef Albers taught her to see, but her abstract art shows the influence of his devotion to color and nested squares as well.

She also worked in the college laundry, and she used ink stamps meant for sorting as tools for drawing. It was the closest she ever came to conceptual art, but already repetitive in the extreme, one bed linen or shirt after another. Later, with kids in school, she picked up on the pleats in their clothing. The curators, Kim Conaty and the Menil Drawing Institute's Edouard Kopp, speak of the found and transformed. They also arrange the show by themes, although I have trouble telling them apart. Still, it suits an art so determined that it barely changes from her return to California to her death in 2013.

She loved dance, but not as a collaborator among friends like Robert Rauschenberg. She was instead a lifetime learner, and she learned from everything. Her forms within forms include tree rings in the regions redwood forests, but she was just as fond of plane trees in the city, in Golden Gate Park. For Asawa, it gets hard to separate nature and culture, no more than fish scales and laundry stamps. Other sections of the show speak of rhythms and growth patterns—patterns that she could have discovered or imposed. Maybe both at once.

She took her notebooks with her wherever she went, looking to fruit for its ripeness and the tides for their waves. The first, like the zigzags of folded paper, bring in color, but her drawings largely stick to black and white, much like her wire. She made incisions in felt tips to maintain the look of calligraphy in pen and ink. Sketches include portraits as well, looking inward and outward. Her subjects are thoughtful and vulnerable, the qualities she must have valued most in art. In the words of another of the section titles, they are the qualities of curiosity and control.

Asawa's art can feel fussy and claustrophobic. Even in sculpture, it took Gego before her and Nengudi to come to show how nested shapes could flex and bend of its own weight. Sometimes, though, what she saw rescued her from all that she was hoping to do. As Paul Cézanne said about Claude Monet, she was "only an eye but what an eye." The same chairs that bring the texture of wood also temper the fuss by appearing in her work as white silhouettes. While her drawing has mass, her wire is light enough to suspend from a thread.

Gego ran at The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum through September 10, 2023, Ruth Asawa at The Whitney Museum of American Art through January 15, 2024.