1.3.25 — The Next Big Thing

From the start, Thomas Schütte was destined to be the next big thing, and he delivers big things as well. Now if only the little things mattered along the way. For conceptual art that keeps you thinking, turn instead to Rodney Graham. And I work this together with a recent report on Graham and another class clown, KAWS and the KAWS collection, as a longer review and my latest upload. Is Graham, too, just clowning around? I am not so sure, but first to Schütte.

One can hear the expectations in his titles—Large Wall, Large Wallpapers, Large Spirit, Father State, and Mother Earth. One can see it in his care to recycle his themes often enough to spread the word. One can hear it words, traced on the wall above the entrance to his exhibition at MoMA,  through January 18. Alles in Ordnung, he writes in simulated jet trails, perhaps on his way to an international career. “All Is in Order,” which is only fair when all is in his hands. Once inside, things can only get bigger.

through January 18. Alles in Ordnung, he writes in simulated jet trails, perhaps on his way to an international career. “All Is in Order,” which is only fair when all is in his hands. Once inside, things can only get bigger.

That large wall simulates a brick wall, interrupted by another wide passage between rooms, in simulated bricks akin to dozens of monochrome paintings. Just before it, the twelve and a half foot bronze of the father state faces visitors with an ample robe and impassive smile. Trust me, it says, but do not even think to get past me. Born in 1954, Schütte lived through the fall of the Berlin Wall and the creation of a larger state, with grand new construction and memorials to match. The artist has no patience for such politics, power grabs, and platitudes, but he matches them in every way. It is what makes his work conceptual but reassuringly material.

Schütte has not had nearly the presence in New York that he has found with European fairs and collectors. Even close followers of contemporary art may be surprised to find him in the museum’s largest exhibition space. His large work and frequent repetition make a visit quick and easy all the same. Works appear in no obvious order, least of all chronological, which is only fair. The greatest number date from close to when his expectations began. He painted and sculpted his own grave in 1981, with a death date of 1996, because he gave himself fifteen years to make it big, and that’s that.

He came up just when art was taking on its own new expectations, which could easily have excluded him, but Schütte caught on and made it his subject. For the curators, Paulina Pobocha with Caitlin Chaisson, art was seeing the decline of Minimalism and a surge of conceptual art, but plain old realism was just too appealing for him to pass up. Perhaps, but he could never let go of anything. He studied at the Academy in Düsseldorf with Gerhard Richter and a stellar cast, including Katharina Fritsch, Isa Genzken, Andreas Gursky, and Thomas Struth. Richter could have shown him how the lushest of paintings, abstract or representational, could pose intellectual puzzles. Struth showed how the art of museums could pose the same questions, Gursky how large projects could remake the human landscape.

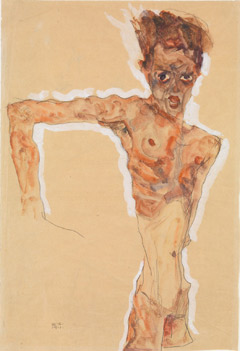

He was fine all along with Minimalism, but it had to be at least halfway conceptual. He paints with a single color on swatches of fabric or plaster, and his wallpaper has delicate verticals that recall Daniel Buren, but with an overlay of stains and brush marks. He starts with more strictly conceptual art, but it has to be skillful as well. He gives himself a day apiece and no more for self-portraits, just as he gave himself fifteen years to succeed. He sketches Valium, like Andy Warhol with a heavier dose of anxiety and irony. Don’t worry, and for god’s sake be happy.

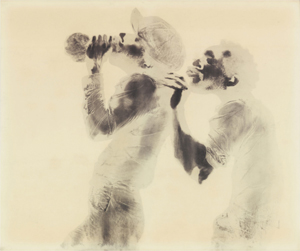

Still, he built his reputation on sculpture. Genzken had shown how portrait busts can look makeshift and sloppy, and Schütte fashions a man lost at sea from oozing polyester and clay. Almost immediately, though, busts acquire a fine polish in ceramics or bronze. Most are of women, with their heads down in a vain search for comfort and rest. Some are men, as Strangers or Jerks. Both are an assault on the pretensions of public sculpture.

Schütte is less well known for full-length figures like Father State and Mother Earth, but they, too, can look grand while refusing to play the hero. Some have a silvery finish on comic-strip body armor or bulging muscles, but in poses that all but shout torment. The busts can rest on pedestals or shipping crates. He has much the same love-hate relationship with architecture old and new, including models of museums and mansions that will never be built. A concrete cylinder could be a bomb shelter, but then it emits dog yelps like another kind of shelter entirely.

From realism and public works to conceptual puzzles and Modernism’s last gasp, Schütte is showing off. Long after his self-portraits, his real subject is himself. He obsesses over it, with no end of sketches and prints. Take what pleasure you like in oversized slices of watermelon as Melonely, and do not take too seriously the hints of melancholy and loneliness. Do take seriously or comically an artist at home and in his studio, with a clothes closet, a rack for socks, miniature easels, and pitifully small collectors. It is not easy being a great artist, but Schütte will do, he promises, whatever it takes.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.