Just a Little Surreal

John Haberin New York City

Sixties Surreal, Pop Art, and Kennedy Yanko

A camel, Nancy Graves liked to say, should not exist. At the very least, a camel should not introduce American art from the 1960s, a time of abstraction on the one hand and pop culture imagery on the other. Yet Graves herself brings three of the species to the Whitney, in sculpture, right out front of "Sixties Surreal." As the title suggests, they and the art within look just a little surreal, and you may wish for something more like the world you thought you knew.

Graves looks at home, too, with life-size animals twisting gracefully in the desert sun. Come to think of it, the 1960s may have had a soft spot for the desert air. Critics called for rigor in late modern art, and zoologists spared no pains to come up with an evolutionary strategy for desert scarcity.  The first public television station had debuted less than a decade before. Meanwhile artists looked to popular entertainment for guidance as never before. Pop Art, it seemed, was here to stay.

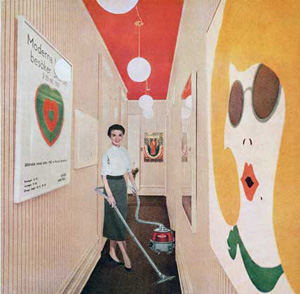

The first public television station had debuted less than a decade before. Meanwhile artists looked to popular entertainment for guidance as never before. Pop Art, it seemed, was here to stay.

Sometimes life itself can get just a little surreal. I speak with Trump as president, and it makes "Sixties Surreal" difficult to ignore. It can also make compromise that much more abhorrent, and Pop Art did not simply embrace big media. It called for critical scrutiny as well, and the Whitney tells its story. It just may try way too hard for a second Surrealism. As a postscript, half a century after James Rosenquist, Kennedy Yanko is still chasing big gesture and that PoP Art symbol of American dynamism, the automobile.

Mojo secrets

Nancy Graves does not seem especially wrapped up in desert secrets, high-brow or low. Nor does she run especially counter to the period's ethical or artistic standards. A child of the 1960s like me, people assumed, learned from zoos rather than abused animals. Graves makes good use, too, of artistic standards in a camel's anatomy and surface texture. She conceives the space of the museum as an oasis as well. If you do not find that right for the hey-day of Walt Disney, look again.

Dan Nadel, Laura Phipps, and Elisabeth Sussman as curators are not alone either in looking back to American Surrealism and Surrealism in painting. Europeans like Max Ernst and Salvador Dalí had emigrated to America and contributed to the birth of Abstract Expressionism. A 1966 show of "The Other Tradition" in Philadelphia, the Whitney argues, lent scholarship and street cred to Pop Art. That said, the Whitney seems little interested in Pop Art as many see it now. Looking for Roy Lichtenstein, Tom Wesselman, Jim Dine, George Segal, Philip Guston, Alex Katz, or Larry Rivers? You will not find them here.

You will, though, find a lot not often linked to Pop Art or Surrealism. Together, they become a near replay of twentieth-century American art—and a total mess. Do not even try to predict what comes next. Raymond Saunders and Joan Semmel stand up for abstraction, the bright and brushy kind, but rooms apart. Video appears with a whole room for Edward Owens, new to me, and memories of his family, I have no idea why.

It is part of a concerted effort to place art in context of the artist's physical and cultural identity. It gets brutal. The very first room features a painting, poster style, by Jim Nutt in which a woman takes pleasure in the act of castration. Martha Rossler crops a painting of what could be her own flesh, as Hot Meat. Mass culture, she makes it clear, presents women as hot meat every day. Paul Thek makes sculpture in the shape of bone, exposing dripping marrow.

The next full room pictures "Flesh and Bones." It continues with artists known for the third dimension, like Louise Bourgeois, Yayoi Kusama, Lee Bontecue, Eva Hesse, and Bruce Nauman. Assemblage here means a frontal physical posture, like folk art for the machine age. It appears with Edward Kienholz, Lucas Samaras, Niki de Saint Phalle, and Marisol. H. C. Westermann, who appears more than any other artist, is their patron saint. It makes perfect sense Claes Oldenburg devotes soft sculpture to a toilet.

In approaching the body, art like this makes good use of deception. Kay Sekimachi and Lynn Hershman Neeson alike depict human hair, but with nylon and feathers. Blond wood frames faux blond hair for Luis Jimenez as well. Rigid materials from Barbara Chase-Riboud descend to the floor in the shape of a soft black dress. Betye Saar has her Ten Mojo Secrets. Alex Hary could fit it all into a large empty pretend paper bag.

Shows of force

Where Surrealism was an art of dark visions, PoP Art was an art of bright ideas—and where Surrealism was at the heart of early modern art, Pop Art was gamely postmodern. "Sixties Surreal" does its level best to reconcile the two. Andy Warhol is allowed in, with his Marilyn,  but with just two versions, both of them dark gray. Robert Rauschenberg does not appear at all. Electric black and white lend an icy chill to images out of the movies for James Rosenquist and Deborah Remington. Colors threaten to deface a woman for Anita Steckel, while photography in silhouette crosses a city for Senga Nengudi, leaving it the richer and edgier for the journey.

but with just two versions, both of them dark gray. Robert Rauschenberg does not appear at all. Electric black and white lend an icy chill to images out of the movies for James Rosenquist and Deborah Remington. Colors threaten to deface a woman for Anita Steckel, while photography in silhouette crosses a city for Senga Nengudi, leaving it the richer and edgier for the journey.

The show is dangerously short of clear ideas and robust laughter. Westermann'a Memorial to the Idea of Man If He Was an Idea tries hard for a smile, but forget it. A cartoon-style painter like Peter Saul does little better. Who would have thought of Robert Smithson, the apostle of earthworks and entropy, as religious? Here he is a green-eyed chimera bearing the stigmata. Token appearances by the likes of Warhol and Rosenquist can go only so far.

For all that, the Whitney is still trying to assign a future to art, along with a recent past. This is a show of ideas, and the biggest idea is diversity. It devotes a room to women's liberation, with collage itself a state of war and a pink shirt for Hannah Wilke a state of mind. The Civil Rights movement appears less concertedly, with blacks like Chase-Riboud and Saar scattered about. Romare Bearden contributes one of the darker shinier canvases, like a mirror. This show is big on beliefs, but not terribly good at articulating them.

And then there is a room for "Show of Force," from a decade torn by war in Vietnam. An off-color American flag from Jasper Johns sets against gray shadows. It is among the greatest works of its time. Just try convince yourself it is a war protest. A flag drapes a black man like a corpse for Benny Andrews as No More Games. It would be about time.

Did war play out on TV? So did a treacherous mix of mass culture and fine art. Photography appears most in a room for "Social Surrealism," from a decade in which social context meant nothing less than Surrealism, and sculpture for Robert Arneson could be a camera or a phone. Diane Arbus and Lee Friedlander photograph faces right off TV, and it is hard to know which to call masks. Is it nothing more than art about art? Ever since, self-reflection has been the order of the day.

The Whitney has too few dreams for Surrealism and too little snap crackle and pop for Pop Art. It has too many artists taking it away from either one—and too many names it could live without. It is too caught up in ritual repetition and the darkness. It could be a bad idea to try to sum up a decade like this one anyway, and it never finds an overarching narrative to help. What it does have is the vital tension tearing it apart. Do not forget to dress for the hot desert air.

Speeding right along

When John Chamberlain made sculpture from used car parts, he inherited all the dynamism of a speeding car and all the gravity and perfection of a showroom. He could count, too, on a different kind of dynamism and stasis, that of postwar American art. If he was throwing the scraps of sculpture every which way, Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and others were hurling and slathering paint. If he was welding them into something larger, so were Dorothy Dehner and David Smith, starting at an auto plant. If he was also adopting an icon of what had become in no time the classic American lifestyle, so were James Rosenquist and Pop Art. America, boosters felt, was in motion like no other country, but it was not going anywhere if that meant going away.

Kennedy Yanko makes art not a bit larger than life. It has all the quick moves in converting a gallery into a showroom and a showroom into a highway. One work has rods sticking out in every direction, badly in need of repair. Others have gentle folds from surfaces of welded steel. Black is the dominant color, in what I took for industrial-strength spray paint. Rent a limo in Tribeca now.

Yanko, though, is a designer, not a destroyer. His show fits easily on gallery walls and on pedestals, like scale models for something larger. He cultivates the look of fine design as well. These materials hold out hope that one could double them over by hand, without need of a hammer or blowtorch. Folded white has the texture of fabric rather than metal. Silvery surfaces make a point of shining.

The gallery lists only generic metal and, new to me, paint skin. Paint, it explains, accumulates on whatever it covers to the point that he can dispense with backing. Jack Whitten, the black artist, does much the same with acrylic on plastic before transferring it to painting. If Whitten is decidedly abstract, so is the generation that Yanko recalls. You call this painting? Well, yes.

Not that Chamberlain is devoid of trickery or artistry. If you have not seen his work in a while, you can easily have forgotten just how monumental and how pliable sculpture can be. You can forget how good he is as a pure painter. Series have stuck to mere arches and to black or twisted and cut into space itself. It is not out to barrel down the highway and ram into you from behind. Oh, and Whitten made sculpture, too.

Yanko is up to much the same thing, at a time when so much in the galleries seems like old news. He just happens to do it well, with an eye on art's image of America. If it is a little too nice and a little too old, so be it. At the same gallery two doors down, Claudia Alarcón paints with actual tapestries, in conjunction with a South American collective, from the town of Silät, of her own devising. Yanko, though, pushes it harder even without the plea for cultural diversity. He also calls his show, "Epithets," and there are a lot of names and terms here to throw around.

"Sixties Surreal" ran at The Whitney Museum of American Art through January 19, 2026. Kennedy Yanko ran at James Cohan through May 10, 2025.