12.30.24 — The Shadow of Death

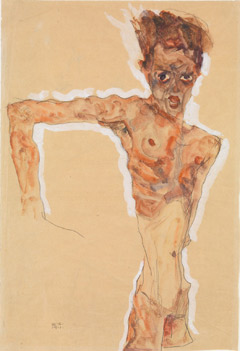

Egon Schiele grew up in the shadow of sex and death, but it took him until he turned twenty to make them the stuff of his art. He hardly changed for the rest of his life. He had little choice, for he never reached age thirty. Besides, sex and death kept him busy enough along the way.

His father died of syphilis, and his parents suspected him and his sister of playing around. He formed relationships on his own terms and expected an open marriage. When that failed, he and his wife left Vienna for a town where their house became a haven for teenage girls. Arrested for seduction, he could have spent the rest of his life in prison, but the authorities settled for a charge of possession of pornography—more than a hundred drawings from his own hand. He walked free just in time for conscription in World War I. He died of the flu epidemic in 1918.

You may remember him for a painting of Death and the Maiden. Suffice it to say that they are in bed together, and the Schubert string quartet goes unheard. You may remember him that much more for obsessive self-portraits, often nude. Gaunt arms and hands extend to frightening proportions, their joints red with pain and the little flesh that remains touched by a gangrenous green. The Neue Galerie, though, sees his move from the big city as a return to a more idyllic childhood. It sees landscape painting and drawing as the one constant in his art, “Living Landscapes,” through January 13.

The exhibition includes photos of Schiele and poems expressing his dark, conflicted relationship with earth and sky. In reality, he was a handsome, charismatic young man, although always brooding. On coming to Vienna, he sought support from Gustav Klimt and Oskar Kokoschka, and he got it. He exhibited with the first wave of Austrian Expressionism, the Vienna Succession, in 1909. Administrative duties in World War I kept him from painting, but also from combat, and he continued to exhibit widely, in Vienna, Paris, and Berlin. If he had settled outside Austria’s legal and cultural capital as well, no one more relished the pose of the outsider in art or life.

A room for his early years does not look all that promising. Had Schiele died in 1910, like Paula Modersohn-Becker three years before, he might be remembered today as a Symbolist or not at all. When he paints landscape as a teen, it has little to do with nature. Dark compositions flecked by light look like nothing so much as Le Moulin de la Galette, from Pablo Picasso in 1900, when he, too, was anything but revolutionary. Schiele himself might have wondered if he would ever lighten up. Fortunately, he rediscovered sex and death.

For the 1909 Vienna art show, he contributed a painting of Danaë—smushed to the ground, but still a bloated white. Zeus came to her in a golden shower, but Schiele cuts out the gold and the rejuvenating rain. Soon enough, too, he introduces men. Lovers share a bed, seen from above or from nowhere at all, their long limbs at impossible angles. When he works on paper, the ground is as stained as the bodies. All he lacks is the gangrene, and that, too, is on its way.

Just months ago, the museum boasted of Klimt landscapes, but the show delivered far more than it promised. So does this one. A central room has landscapes to either side of the mantel, but with a visitor’s back to them coming in. Check out one, though, and its trees cast their branches everywhere—continuing as cracks in the soil, like a self-portrait with cracked skin. On paper, a thin, bare tree bears a spot of red, much like the artist’s knuckles. Could landscape have played a central role after all?

The last room follows him to the towns where he moved, and there, too, he has mixed feelings about the land. He lingers over a medieval town with its houses and spires, but with nowhere for him to stand, to observe, or to live. Distant hills have the angled blue facets of an iceberg. The town itself becomes a confusion of colors and geometries. And that confusion continues into paintings of a steel bridge and an equally massive mill. This may be landscape, but, yes, a living landscape, a place for the stubborn desires of modern life.

More than once, he returns to sunflowers. Had he developed a fondness for Vincent van Gogh and the gentle light of southern France? Yes again, and he admired van Gogh no end at an exhibition in Vienna. Still, he sticks to muter colors, and a rising or setting moon looms on the horizon like a distant eye. But then van Gogh, too, had his private terrors. And Schiele’s flowers, unlike those in a still life, are rooted in the earth as he could never be in art or in life.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.