8.4.25 — A Celebration of Deliverance

It could be talking about New York. It tells of a city, a port city, open to the world. You can find pretty much anything here and anyone.

It is a prosperous city and an educated one, although not everyone speaks the same language. It is always under construction, with an eye to creating public spectacles and public spaces, and housing does not welcome everyone everywhere. It has, if anything, too many artists. Above all, it values diversity and tolerance where other states may not, with no shortage of synagogues to match. As happens, though, it is Amsterdam, the city of “The Book of Esther in the Age of Rembrandt,” at the Jewish Museum through August 10—and I work this together with an earlier report on finding freedom under Baroque Spain with Juan de Pareja and Diego Velázquez as a longer review and my latest upload. Now what happens if everyone here claims the Bible’s lessons as one’s own?

The Book of Esther has that rarity in the Hebrew Bible, a happy ending, but with conditions. It is a tale of threats, deliverance, and celebration, and Amsterdam had every right to celebrate. It had at last won its freedom from Spain, as a republic, in time for the great age of Dutch painting, and it saw Esther as about nothing less. History often singles out Rembrandt for his sympathy for Jews, Ashkenazi and Sephardic, and he lived in a quarter that they, too, occupied—although that may have had more to do with an artist’s income and with official decrees limiting Jewish life while guaranteeing freedom of worship. Prints of Rembrandt’s wife, Saskia, have come to be known as The Jewish Bride. Here, though, the city takes credit.

A Jewish heritage, I might argue, is divided over Esther, too. After the fall of Israel, the Babylonian captivity, and a second conquest by still another empire, Persia, Jews were at last free to go home, but should they, and where is home? Should it lie in a capital for all the people, with the temple and its sacrifices? Or should it lie in the word of God and the law wherever they may be? Where the books of Ezra and Nehemiah demand a community apart, Esther is about living under foreigners, even marrying one. It might speak to the Dutch—or to New Yorkers today.

Do Jews celebrate on Purim to remember their deliverance from a royal decree of death? The Jewish Museum opens with a room for both aspects of remembrance, the story and the place. It has scrolls of the book of Esther, one of the Old Testament’s shortest, to be read aloud on the holiday, and stone fireplace guards with images. It has Delft tiles and silver to help in getting drunk, as the occasion dictates. It has prints of synagogues and a public square with a new town hall in progress. No one seems to be merely idling or, conversely, in a hurry passing through.

Only slowly do paintings take over the story, and they never stop. Near the end, a wooden chest bears small paintings of Esther, enough to call it a book in itself. Do Flemish artists also tackle Esther with crisper, shinier colors? So much for the exhibition’s political history, but then they do reflect a greater hierarchy of kings and attendants. A prominent Dutch painter, Jan Steen, illustrates the tale’s climactic revelation three times. He, too, has brighter lights, along with hokier gestures but a gift for composition.

Above all, here comes the circle of Rembrandt, especially a late student, Aert de Gelder. He can imitate his teacher’s bulky fabrics filling out the promise of female anatomy, but not the softer outlines and inward-directed eye. Where his Esther looks up, toward her god, or to the king, Rembrandt’s looks nowhere but within. So he does, too, in a self-portrait on loan from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston (which lost a Rembrandt years ago to a still unsolved theft along with a Vermeer), at age a mere twenty-three. Its firm but parted lips speak of a young man’s confidence and a trembling inner light. The misty darkness of Rembrandt’s late portrait at the Frick Collection is still to come.

That leaves a major gap, Rembrandt’s Bible. You may well wonder where to find it, but the show has a whole room for a standing Esther simply thinking. It is a fraught moment. You may recall that Haman, an advisor to King Ahasuerus, takes offense when a Jew, Esther’s cousin Mordecai, refuses to bow to someone other than the one true god—and in return extracts a death sentence for the Jews. Offended that his wife did not show proper obedience either, Ahasuerus ditches her in favor of Esther, without knowing Esther’s faith. In the painting, she is preparing to tell him.

She will do so, obtaining a death sentence for Haman and a promise of deliverance, although it is a complicates story. (Can Ahasuerus go back on his own word?) And paintings mostly zero in the confrontation, with the bad guy in darkness and the king in the light. Rembrandt shows only Esther and an elderly attendant, and here the older woman is lost in shadow, while Esther is lost in her fears, in her determination, and in thought. Anticipation becomes drama. Rembrandt, around age thirty, has a lot of thinking to do himself.

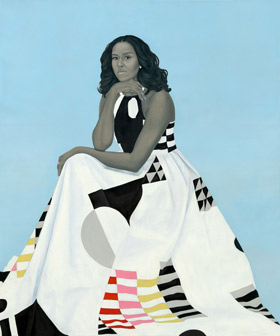

Still, a large exhibition has a hole at its very center, and there is no getting around it. Not even Rembrandt, largely in his absence, can steal the show. The curator, Abigail Rapoport, does have a 1992 painting by Fred Wilson, who compares Queen Esther to Harriet Tubman. African Americans and other contemporaries can claim the story as a parable of deliverance, too. Yet New York has already had shows of the Rembrandt’s influence, and followers look if anything more awkward here. It is a fascinating story all the same, of a solitary Esther and a busy, unshaken city.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.